The impending Obama administration decision on the Keystone XL Pipeline, which would tap into the Athabasca Oil Sands production of Canada, has given rise to a vigorous grassroots opposition movement, leading to the arrests so far of over a thousand activists. At the very least, the protests have increased awareness of the implications of developing the oil sands deposits. Statements about the pipeline abound.

Jim Hansen has said that if the Athabasca Oil Sands are tapped, it’s “essentially game over” for any hope of achieving a stable climate. The same news article quotes Bill McKibben as saying that the pipeline represents “the fuse to biggest carbon bomb on the planet.” Others say the pipeline is no big deal, and that the brouhaha is sidetracking us from thinking about bigger climate issues. David Keith, energy and climate pundit at Calgary University, expresses that sentiment here, and Andy Revkin says “it’s a distraction from core issues and opportunities on energy and largely insignificant if your concern is averting a disruptive buildup of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere”. There’s something to be said in favor of each point of view, but on the whole, I think Bill McKibben has the better of the argument, with some important qualifications. Let’s do the arithmetic.

Jim Hansen has said that if the Athabasca Oil Sands are tapped, it’s “essentially game over” for any hope of achieving a stable climate. The same news article quotes Bill McKibben as saying that the pipeline represents “the fuse to biggest carbon bomb on the planet.” Others say the pipeline is no big deal, and that the brouhaha is sidetracking us from thinking about bigger climate issues. David Keith, energy and climate pundit at Calgary University, expresses that sentiment here, and Andy Revkin says “it’s a distraction from core issues and opportunities on energy and largely insignificant if your concern is averting a disruptive buildup of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere”. There’s something to be said in favor of each point of view, but on the whole, I think Bill McKibben has the better of the argument, with some important qualifications. Let’s do the arithmetic.

There is no shortage of environmental threats associated with the Keystone XL pipeline. Notably, the route goes through the environmentally sensitive Sandhills region of Nebraska, a decision opposed even by some supporters of the pipeline. One could also keep in mind the vast areas of Alberta that are churned up by the oil sands mining process itself. But here I will take up only the climate impact of the pipeline and associated oil sands exploitation. For that, it is important to first get a feel for what constitutes an “important” amount of carbon.

That part is relatively easy. The kind of climate we wind up with is largely determined by the total amount of carbon we emit into the atmosphere as CO2 in the time before we finally kick the fossil fuel habit (by choice or by virtue of simply running out). The link between cumulative carbon and climate was discussed at RealClimate here when the papers on the subject first came out in Nature. A good introduction to the work can be found in this National Research Council report on Climate Stabilization targets, of which I was a co-author. Here’s all you ever really need to know about CO2 emissions and climate:

- The peak warming is linearly proportional to the cumulative carbon emitted

- It doesn’t matter much how rapidly the carbon is emitted

- The warming you get when you stop emitting carbon is what you are stuck with for the next thousand years

- The climate recovers only slightly over the next ten thousand years

- At the mid-range of IPCC climate sensitivity, a trillion tonnes cumulative carbon gives you about 2C global mean warming above the pre-industrial temperature.

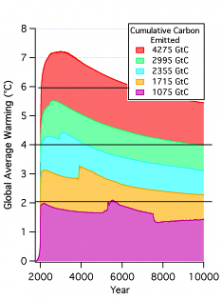

This graph gives you an idea of what the Anthropocene climate looks like as a function of how much carbon we emit before giving up the fossil fuel habit, without even taking into account the possibility of carbon cycle feedbacks leading to a release of stored terrestrial carbon  The graph is from the NRC report, and is based on simulations with the U. of Victoria climate/carbon model tuned to yield the mid-range IPCC climate sensitivity. Assuming a 50-50 chance that climate sensitivity is at or below this value, we thus have a 50-50 chance of holding warming below 2C if cumulative emissions are held to a trillion tonnes. Including deforestation, we have already emitted about half that, so our whole future allowance is another 500 gigatonnes.

The graph is from the NRC report, and is based on simulations with the U. of Victoria climate/carbon model tuned to yield the mid-range IPCC climate sensitivity. Assuming a 50-50 chance that climate sensitivity is at or below this value, we thus have a 50-50 chance of holding warming below 2C if cumulative emissions are held to a trillion tonnes. Including deforestation, we have already emitted about half that, so our whole future allowance is another 500 gigatonnes.

Proved reserves of conventional oil add up to 139 gigatonnes C (based on data here and the conversion factor in Table 6 here, assuming an average crude oil density of 850 kg per cubic meter). To be specific, that’s 1200 billion barrels times .16 cubic meters per barrel times .85 metric tonnes per cubic meter crude times .85 tonnes carbon per tonne crude. (Some other estimates, e.g. Nehring (2009), put the amount of ultimately recoverable oil in known reserves about 50% higher). To the carbon in conventional petroleum reserves you can add about 100 gigatonnes C from proved natural gas reserves, based on the same sources as I used for oil. If one assumes that these two reserves are so valuable and easily accessible that it’s inevitable they will get burned, that leaves only 261 gigatonnes from all other fossil fuel sources. How does that limit stack up against what’s in the Athabasca oil sands deposit?

The geological literature generally puts the amount of bitumen in-place at 1.7 trillion barrels (e.g. see the numbers and references quoted here). That oil in-place is heavy oil, with a density close to a metric tonne per cubic meter, so the associated carbon adds up to about 230 gigatonnes — essentially enough to close the “game over” gap. But oil-in-place is not the same as economically recoverable oil. That’s a moving target, as oil prices, production prices and technology evolve. At present, it is generally figured that only 10% of the oil-in-place is economically recoverable. However, continued development of in-situ production methods could bump up economically recoverable reserves considerably. For example this working paper (pdf) from the National Petroleum Council estimates that Steam Assisted Gravity Drainage could recover up to 70% of oil-in-place at a cost of below $20 per barrel *.

Aside from the carbon from oil in-place, one needs to figure in the additional carbon emissions from the energy used to extract the oil. For in-situ extraction this increases the carbon footprint by 23% to 41% (as reviewed here ) . Currently, most of the energy used in production comes from natural gas (hence the push for a pipeline to pump Alaskan gas to Canada). So, we need to watch out for double-counting here, because our “game-over” estimate already assumed that the natural gas would be used for one thing or another. A knock-on effect of oil sands development is that it drives up demand for natural gas, displacing its use in electricity generation and making it more likely coal will be burned for such purposes. And if high natural gas prices cause oil sands producers to turn from natural gas to coal for energy, things get even worse, because coal releases more carbon per unit of energy produced — carbon that we have not already counted in our “game-over” estimate.

Are the oil sands really the “biggest carbon bomb on the planet”? As a point of reference, let’s compare its net carbon content with the Gillette Coalfield in the Powder river basin, one of the largest coal deposits in the world. There are 150 billion metric tons left in this deposit, according to the USGS. How much of that is economically recoverable depends on price and technology. The USGS estimates that about half can be economically mined if coal fetches $60 per ton on the market, but let’s assume that all of the Gillette coal can be eventually recovered. Powder River coal is sub-bituminous, and contains only 45% carbon by weight. (Don’t take that as good news, because it has correspondingly lower energy content so you burn more of it as compared to higher carbon coal like Anthracite; Powder River coal is mined largely because of its low sulfur content). Thus, the carbon in the Powder River coal amounts to 67.5 gigatonnes, far below the carbon content of the Athabasca Oil Sands. So yes, the Keystone XL pipeline does tap into a very big carbon bomb indeed.

But comparison of the Athabaska Oil Sands to an individual coal deposit isn’t really fair, since there are only two major oil sands deposits (the other being in Venezuela) while coal deposits are widespread. Nehring (2009) estimates that world economically recoverable coal amounts to 846 gigatonnes, based on 2005 prices and technology. Using a mean carbon ratio of .75 (again from Table 6 here), that’s 634 gigatonnes of carbon, which all by itself is more than enough to bring us well past “game-over.” The accessible carbon pool in coal is sure to rise as prices increase and extraction technology advances, but the real imponderable is how much coal remains to be discovered. But any way you slice it, coal is still the 800-gigatonne gorilla at the carbon party.

Commentators who argue that the Keystone XL pipeline is no big deal tend to focus on the rate at which the pipeline delivers oil to users (and thence as CO2 to the atmosphere). To an extent, they have a point. The pipeline would carry 500,000 barrels per day, and assuming that we’re talking about lighter crude by the time it gets in the pipeline that adds up to a piddling 2 gigatonnes carbon in a hundred years (exercise: Work this out for yourself given the numbers I stated earlier in this post). However, building Keystone XL lets the camel’s nose in the tent. It is more than a little disingenuous to say the carbon in the Athabasca Oil Sands mostly has to be left in the ground, but before we’ll do this, we’ll just use a bit of it. It’s like an alcoholic who says he’ll leave the vodka in the kitchen cupboard, but first just take “one little sip.”

So the pipeline itself is really just a skirmish in the battle to protect climate, and if the pipeline gets built despite Bill McKibben’s dedicated army of protesters, that does not mean in and of itself that it’s “game over” for holding warming to 2C. Further, if we do hit a trillion tonnes, it may be “game-over” for holding warming to 2C (apart from praying for low climate sensitivity), but it’s not “game-over” for avoiding the second trillion tonnes, which would bring the likely warming up to 4C. The fight over Keystone XL may be only a skirmish, but for those (like the fellow in this arresting photo ) who seek to limit global warming, it is an important one. It may be too late to halt existing oil sands projects, but the exploitation of this carbon pool has just barely begun. If the Keystone XL pipeline is built, it surely smooths the way for further expansions of the market for oil sands crude. Turning down XL, in contrast, draws a line in the oil sands, and affirms the principle that this carbon shall not pass into the atmosphere.

* Note added 4/11/2011: Prompted by Andrew Leach’s comment (#50 below), I should clarify that the working paper cited refers to recovery of bitumen-in-place on a per-project basis, and should not be taken as an estimate of the total amount that could be recovered from oil sands as a whole. I cite this only as an example of where the technology is headed.

Interesting piece. I covered many of these ideas (the resource vs. reserve issue in particular) in my post here: http://andrewleach.ca/oilsands/on-the-potential-for-oilsands-to-add-200ppm-of-co2-to-the-atmosphere/

Andrew

In short: to solve the climate problem we must stop burning carbon. Since we are unlikely to dig or pump much of it up just as a passtime, this means Leave It In The Ground.

Big Carbon will resist will all their money.

Thanks so much for this good arithmetical work! And thanks to all who are joining in this fight. For those who can make it at 2 pm on Sunday we will ring the white house in protesters, all bearing quotes from Barack Obama 2008. Let’s see if we can rouse that spirit again

Thanks for this– those of us here in Nebraska and everywhere else under our common sky appreciate it!

I’ve been following the news on climate change since 1987.I’m familiar with the writings of Bill McKibben, Andrew Revkin, and Peter Ward, amongst many,many others.I firmly believe that extraction of the tar sands oil is a very bad idea.I also firmly believe that the planet could reach 1000 ppm by the year 2150.This figure would include the release of terrestial stored carbon from feedback mechanisms such as the thaw of methal hydrates, permafrost, and the increased severity and intensity of wildfires, plus the predicted dieback of the Amazon dues to drying effect.I am an amateur layman, and RealClimate is gracious enough to allow me to post.For me, a 1000 ppm settling point, albeit including the feedback mechanisms, is effective

ly game over for the planet as we know it.

Mark J. Fiore

Harvard, 1982

Boston College Law School, 1987

The next thought on from “Leave it in the Ground” has to be what has to change in the way that governments currently support exploitation of fossil fuels. The oil sands in particular are a massive transfer of shared resources to private companies. The profits are huge, because the rights are being more or less given away, in comparison with the money to be made. I was at a talk yesterday by David Schindler, who’s been at the centre of monitoring the contamination from the oil sands in Alberta. He points out that really we should be ridiculing the people of Alberta for being such fools, because they’re getting almost nothing out of the deals. Oh, and actually it’s mostly lands that were given to first nations through treaties many years ago, which means the Provincial and Federal Canadian governments are also shredding their treaty obligations in the rush to hand over the exploitation rights in a massive firesale.

So the only way to leave fossil fuels in the ground is for governments to set a very high price on expoitation rights, so that every other avenue for energy development gets developed first. At the moment the profits are way too high for anyone to resist the party. Which by the way, connects the fight over the pipeline with the Occupy Wall Street movement. Because it isn’t the 99% who are going to benefit from these massive windfall profits.

Keystone XL is by no means the end of the story. There are two alternative transportation options on the table, the Northern Gateway pipeline through northern British Columbia and the expansion of the Kinder Morgan pipeline through Vancouver. I’m pleased to say that both of these projects are opposed by the majority of people, including First Nations, in British Columbia and there’s a good chance that neither project will materialize. there’s a good chance that both will not materialize. While options remain open (the possibility of doing more upgrading in Alberta and the use of existing pipelines and rail transport to the US) nixing KXL will be a significant impediment to accelerated development of the tar sands in the medium term and an increase in the chance that the Athabasca bitumen will stay in the ground for ever.

In addition to supporting the outstanding work Bill McKibben and 350.org are doing to promote Tar Sands Action, James Hansen also recently said of another environmental organization: “If you want to join the fight to save the planet, to save creation for your grandchildren, there is no more effective step you could take than becoming an active member of this group.” The organization he was referring to is Citizens Climate Lobby: http://www.citizensclimatelobby.org. My experience with them is they are all Dr. Hansen says and more.

I recall back in the days of the optical fiber boom (the one that gave us so many miles of dark fiber because everyone installed all they imagined anyone could need) — the big deal was to get rights of way across state lines and local jurisdictions. Many of the companies purchased rights of way along railroads or power transmission lines where the routes and permissions were already in place.

I’d bet the real interest behind this pipeline might include some notion of later on tapping all that fresh water up in northern Canada for Texas, once a pipeline route is established.

Just speculating.

It would be nice if there could be an edict against burning carbon, or even a stiff penalty imposed, but practical thinking seems to suggest such will not come about.

I suggest that a workable plan would be to develop ways to support the kind of life styles that people choose now without the kind of fuel gluttony that is now the norm. Alternatives that scale up to a meaningful degree are required. Then it might be sensible to ask for carbon dioxide limiting measures.

Campaigning to cancel development of reasonable sources of energy is ludditism, and the impact of this is to cancel industrial activity and, indeed, the state of being that we call the developed world.

I speak not for allowing CO2 to go on unabated; rather I speak for engineering solutions to problems that enable CO2 control. Such solutions could include developing the possibility of stimulating growth of plankton in the oceans; not with a sporadic and half-hearted science demonstration, but instead, a determined and continuing project to accomplish one of the largest scale real solutions. Then we should take away the placebo projects that make people feel good, but will accomplish triviality; such including electric vehicles, solar and wind renewable dreams, and things like smart grids. With a little clarity then being possible, the next things to undertake could be vehicle developments that actually enabled rapid and safe personal transportation with meagre use of fuel.

Most notably might be the acceptance of EPA ratings of vehicles by MPGE according to a formula that is an insult to science, and essentially sets the electric vehicle up as a solution to foreign oil dependence, but ignores the ultimate impact of electric vehicles that is to draw from coal fired electric generation.

Particularly relevant to the Canadian oil sands is the opportunity to change the way water is distributed on the North American continent. This would enable a massive new standing forest project on Federal lands in Western USA, and greatly enhanced agriculture as well.

In the electric power world, the real way to make progress is to first realize the absurdity of centralized power plants that throw away the massive amount of energy as heat due to thermodynamic facts about heat engines. Instead of perpetuating the status quo concepts with enhancing of smart grid enhancements of the electric power infrastructure, we started looking at distributed generation that enabled utilization of discharged heat in cogeneration concepts.

We certainly don’t need the yammering about the evil energy producing folk that maintain the backbone of our continuing (hopefully) industrial revolution. Especially we don’t need yammering that would impede the development of industrial activity that might bring jobs and bring back a sense of prosperity. Without that sense of prosperity, there is no reason to hope for any progress in reducing emissions of CO2.

[Response: Have whatever fantasies you like, but the plain fact of the matter is that full exploitation of the Athabasca Oil Sands is flatly incompatible with having a reasonable chance of holding warming to 2C. You could argue that attacking demand is a more effective way of preventing exploitation than blocking the pipeline (though I don’t see any reason the two efforts are incompatible) but one way or another if you care about climate, you can’t consider the oil sands a ‘reasonable’ energy source. –raypierre]

[Response: Operative word there being “fantasies”. I’ll take the lack of development of the tar sands over your proposed “solutions” any day of the millennium. And the only person tossing the word “evil” around is…you.–Jim]

Thank you for this fine analysis. I have been called several things online when I challenge people who support the pipeline. I can’t wait to post this to facebook! I’ll be in Washington on Sunday to express to the President our shared sincerity in the disapproval of the Tar Sands mining in general and the Keystone XL Pipeline specifically. Hope to see everyone there :-)

Re #10 inline by raypierre

I suggest a rule for problem solving discourse would advise restraint in using debater’s tricks.

[Response: Great idea! You go first.–Jim]

It might have been possible for me to have headed this off by saying, ‘reasonable development of reasonable energy sources’ whereby your ‘full exploitation of the Athabasca Oil Sands’ might not have inspired. I would be inclined to look for something less than ‘full exploitation’ just as I would be inclined to look for moderate use of coal.

It is, however, a fact that coal is at least on a par with the oil sands resources as far as detriment to the CO2 environment, and there is vast and growing rate of usage of this. Either is a problem that needs solution on the demand side of the supply and demand equation, as you recognized. And no, these are not incompatible efforts, but the thing missing here is that all of this is fantasy unless there is a robust economy that can take on the task of solving the whole problem.

I think we can agree that we really do have a big problem on our hands.

[Response: So what’s your point. Coal is bad, it mostly has to stay in the ground. Oil sands are just about as bad (though maybe not as bad as coal-to-liquid). So they have to stay also. Don’t see where the disagreement is. Developing just a little bit of the oil sands is like being a little bit pregnant. –raypierre]

RE: Water to Texas–

TransCanada (the company building the pipeline) has mentioned that it could be switched to carry water.

Those familiar with the aggressive competition for water, especially from Texas and Colorado, do not find this far-fetched at all.

The company is very, very resistant to changing the route of Keystone XL. Since that would effectively split the opposition (or it would have in the past!) one must wonder why TransCanada insists on building over the Ogallala aquifer. In the Sandhills, the aquifer surfaces and in much of the rest of the area, wells can be very shallow.

Let me add a reminder that we are dealing with the Oil Guys here. The culture is ruthless, cutthroat, greed-driven … you know, like those cowboys at BP!

To be blunt, they do not care about a damn thing but their own interests.

As someone who was on the Gulf Coast for the BP blowout, I keep reminding people here in Nebraska about these charming folks. Luckily, they seem to have used enough bullying to make their character clear.

“They would not only sell their mother … they would deliver!”

My message/question to all those conducting this increasingly emotional ‘jihad’ against Keystone XL is – where is the real-world, measurable, quantifiable evidence of the supposedly massive environmental damage and carbon footprint increase, this pipeline will create? To quote the excellent article above, “2 gigatonnes carbon in a hundred years…” The heavy oil industry in your own State of California pumps out vastly larger quantities of carbon than the Alberta Oilsands ever will. Why not invest your energy and rhetoric at the White House this weekend protesting about emissions where they are real and happening today?

Fact is, the risks overall of the Keystone XL pipeline are well-mitigated. The technology and expertise that will be deployed in building the safety mechanisms around this infrastructure project is world-leading. What’s more, TransCanada Pipelines has committed an initial $100m provision to address any leaks that may occur. And there is no reason why a reasonable compromise cannot be achieved with respect to the sensitive regions the pipeline will pass through.

Let’s face the real world of 2011 here – both the US and Canada need Keystone XL. But the US far more so because of the massive economic boost in terms of jobs and much-needed infrastructure, as well as the critical need for longer term energy supply security. Canada and Alberta needs Keystone XL too. However, there is a ready and waiting global market for Canadian energy and supply will gravitate to where demand exists and permits i.e. the Far East and Asia. This shift to the road of least resistance is happening already, at huge economic advantage to Canada and at secure-supply disadvantage to the US.

After all is said and done, at the end of the day Economics will be the final determinant – responsible, environmentally-aware, capitalistic Economics. Therefore I see no solid reasons why Keystone XL should not go ahead. I support the project unequivocally, as should most level-headed Americans.

For some background to why James Hansen believes it will be “game over” if the tar sands are exploited, read his paper: “Implications for Human-Made Climate Change”

http://www.columbia.edu/~jeh1/mailings/2011/20110118_MilankovicPaper.pdf

He argues that the 2 degree Celsius target is not safe. Bill McKibben agrees (hence 350.org, not 450.org).

Re#13

So what’s my point? Things are a lot more complicated.

I do not agree that moderate development of the oil sands is like being a little bit pregnant.

Note also, developing the oil sands is geo-politically better than being dependent on Mid-Eastern oil.

And the emergence of electric vehicles is encouraged by government with apparent acclaim from science, yet this also perpetuates energy guzzling under the pretense of efficiency of electric power. The incremental electric power to drive electric vehicles is, of course, inescapably attached to incremental increase in use of coal in the power plant heat engines.

The apparent acclaim from science is its acceptance of the EPA rules for MPGE, which denies the fact that electricity is fundamentally derived from heat engine operations, where massive heat energy is discharged of necessity, and the formula asserts no such heat discharge.

The usual argument is that, well, electric vehicles will not do anything to reduce CO2, but they will reduce use of oil by shifting to coal as the fundamental source of energy. So never mind that science is insulted.

My real point is that all this accomplishes very little, but appears otherwise. In the face of this there are real things we might do, and these get little notice.

[Response: Your real point is that you have a car you want to market, and electric vehicles and such potentially impinge on that.–Jim]

A cluster of Cedar Elm trees in a draw here in Central Texas have died of the the intermittent exceptional droughts of the last several years. http://earthlightimagery.com/storage/_ARC8153_W.jpg The bark has split away and curled into tubes. It’s a snapshot of widespread deforestation & incipient desertification of the Edwards Plateau.

“A drought for the centuries: It hasn’t been this dry in Texas since 1789” http://texasclimatenews.org/wp/

Oil prosperity here won’t make it rain and won’t pull water out of the ground when it isn’t there. The success of KXL pipeline will be a Pyrhicc victory indeed as climate change turns the means of production into ashes and dust.

Its really a difficult issue. If Keystone is blocked, there is a very high chance the Chineese will get the oil -they are reportedly investing heavily in the tar sands (and just about any other source of oil they can). So we could simply end up shifting where the oil is used, rather than keeping it in the ground.

BTW, those near step function changes in T in the graphs, particularly for 1075 and 1750 look very nonintuitive. Is there a simple explanation for them?

[Response: The comment about the Chinese is a red herring. So far as climate goes it doesn’t matter who gets the oil. The CO2 still winds up in the atmosphere if anybody gets it. And to get it, it has to flow out somewhere (so for those who want to keep it in the ground, every leak has to be fought, not just Keystone XL). But for economics, it doesn’t matter if the Chinese get the oil either. Oil is traded on the world market, so if the oil sands oil is produced at all, it makes no difference whatever if it’s the Chinese that get the oil, since that displaces some other oil they would have used. It is true that extracting oil sands crude increases world supply of oil — but also increases the ultimate world emissions of CO2. To protect climate, some way needs to be found to do without that oil. No two ways about it. You can argue about means, but if you accept that a trillion tonnes is the danger line, then it’s not at all pointless to want to find ways to leave it in the ground. –raypierre]

Could somebody educate me, what kind of life style we should adopt to keep our energy use per capita under 2000W (which is the global average today). I just made a quick calculation that a round trip (5000 mi at 50mi/gallon ~ 300kg kerosene) from New York to San Francisco for an AGU meeting is the equivalent of 400W energy use for a whole year (which is twice the energy use per capita in Bangladesh).

[Response: Well part of the answer to that is better transportation systems and more carbon-neutral energy. If all US participants could go to AGU by high speed train, that would improve matters even if the train were powered by fossil-based electricity. Even better if it’s carbon-neutral energy. (I would mention how France does it, but I don’t want to start a distracting conversation on that). It’s a big job, but it’s one that has to be done anyway, since if the whole world tries to pull itself into prosperity by burning carbon at the rate the US does, then we run out of coal even at the highest estimates by 2100, and you wind up with no fossil energy and the hellish climate you get from 5000 gigatonnes cumulative emission. So since the job has do be done, why not do it before the climate is irrevocably trashed, rather than putting it off? Gee nobody likes to go to the dentist, but an abscessed tooth — you really don’t want to go to that. –raypierre]

Without even reading the post or any of the comments, let me just say OH Em Gee!!! I can FINALLY talk about resources and cliamte without being smacked down!!!!!

OK, I’m chill… I’ll go read now… back soon…

Your estimates of climate sensitivity come from the IPCC, which assumes that aerosols will continue to provide a very strong cooling effect that offsets about half of the warming from CO2, but you are talking about time frames in which we have stopped burning fossil fuels, so is it appropriate to continue to assume the presence of cooling aerosols at these future times? Since we would already be over 2C of warming with current CO2 levels, except for aerosols, isn’t the safe amount of fossil fuels that can be burned zero?

[Response: This is an interesting point that bears thinking about. The 2C warming for a trillion tonnes is for carbon alone, and already factors in an assumption that aerosols go away when you stop burning fossil fuels. The issue, though, is how to reconcile that figure with the amount of warming we’ve seen so far. There, you have to factor in not only the aerosol cooling but the methane (and possibly black carbon) warming, as well as a few other anthropogenic greenhouse gases. One problem is that we don’t know today’s aerosol forcing very accurately. If aerosol forcing is high, then reconciling with recent warming demands very high climate sensitivity (which you see realized after the aerosols go away) — and that would indeed mean we may have already passed the threshold for 2C warming. A trillion tonnes only buys you a 50-50 chance that warming is 2C or less. There is a nice article in GRL by Kyle Armour and Gerard Roe on the interplay of aerosol masking and climate sensitivity. –raypierre]

re #20 – The XL pipeline would have no effect on the amount of oil China removes from the sand, they’ve already made massive investments there and will produce it regardless of the end user. Agree w/ raypierre, fear of China getting it if we don’t is myopic, but rather than fighting TransCanadaXL, it’s the Canadian and Alberta governments that need to be awakened.

Businesses are so successful at winning politically, that they have not had to pay external costs of emitting carbon into the atmosphere. A fair and honest system of paying for carbon and let the market decide if it wants tar sands or not. Not paying for co2 emissions, denying conseqences of AGW results in public protests. Its time for some of the carbon based industries to accept the reality of climate and work it into their business models. If Obama is elected, I believe he will enact the EPA to go ahead with their co2 plan. That in itself will drive down the value of oil sands to the United States.

@16 “And there is no reason why a reasonable compromise cannot be achieved with respect to the sensitive regions the pipeline will pass through.”

Except that Keystone will not compromise. They insist on putting a high pressure pipeline through the Nebraska Sand Hills, buried only 4 feet deep, in an area that is subject to blowouts, especially during droughts. Their Environmental Impact Statement completely ignored the issue, as well as an excellent paper on the subject. See here http://www.sciencemag.org/content/313/5785/345.abstract?sid=fa702e6e-156b-4127-80f3-ce2688451df9

for the abstract. During the last megadrought, this area was active sand dunes, subject to movement of dunes over 10m high. A lousy place for a pipeline, even without the “end of game” carbon issue!

I sincerely hope that you are not serious in maintaining the following:

The peak warming is linearly proportional to the cumulative carbon emitted

It doesn’t matter much how rapidly the carbon is emitted

The warming you get when you stop emitting carbon is what you are stuck with for the next thousand years

The climate recovers only slightly over the next ten thousand years

At the mid-range of IPCC climate sensitivity, a trillion tonnes cumulative carbon gives you about 2C global mean warming above the pre-industrial temperature.

Even the lame IPCC does not try to maintain that warming due to anthropomorphic carbon emissions will result in linear warming. The accepted relationship is exponential.

The warming effect lasting 1000 years is not at all the accepted truth, ie that CO2 has a atmospheric lifetime of 150 years and I believe that s an exaggeration.

The climate only recovers slightly over the next 10,000 years. Excuse me just what were these people smoking to make that claim. the climate has changed considerably more than current trends, with out human intervention in as little as a century.

Please the only trends that deal in absolutes ignores the fact that this figure is still a small percentage of total carbon budget for our home. The claim that the amount is cumulative is not confirmed by the facts.

Why do you continue to print such nonsense. Will the warmers finally admit that their cause is lost, please!

Emanuele Lombardi

[Response: Yes, I’m seriously saying all that. You ought to try reading some of the literature sometime, including the National Research Council report on climate stabilization targets, available free for just clicking on the link. That summarizes the research on which my synopsis is based. You are confusing atmospheric concentration with emissions. Radiative forcing is logarithmic in concentration, but the concentration increases faster than linearly with emissions, since the more you emit, the less is taken up by the oceans and the more remains in the atmosphere. That effect turns out to cancel out the logarithmic behavior, giving you a nearly linear warming (at least up to about 5000 gigatonnes total emissions). All based on fairly simple carbonate/bicarbonate equilibrium chemistry. –raypierre]

Results: See:

http://www.gluckman.com/ChinaDesert.html

Beijing’s Desert Storm

“The desert is sweeping into China’s valleys, choking rivers and consuming precious farm land. Beijing has responded with massive tree-planting campaigns, but the Great Green Walls may not be able to buffer the sand, which could cover the capital in a few years ”

…..article……

I got an email from the Sierra Club today about the Taylorville, Illinois coal to gas plant proposal:

“Dear Edward,

Your senator voted for Tenaska’s coal plant. Urge them to oppose dirty energy!

Like a bad Frankenstein bill that just won’t die, the Taylorville Energy Center is back from the dead and looking for handouts from Illinois ratepayers like you again.

Last Thursday in Springfield, a majority of senators voted to kill the expensive and dirty project and the bill failed. But a motion was filed to reconsider, and the bill will be back for a vote next week.

Unfortunately, your senator voted to support this costly coal plant. Please make sure this risky project is dead once and for all: Contact your senator to share your disapproval and urge them to vote NO when it comes back next week.

…………

Sarah Gulezian

Sierra Club Illinois”

My guess is that it is easier to protest one pipeline than to protest the whole coal industry, but there are people protesting mountaintop removal and coal fired power plants.

21 Balazs: We are not saying you have to go without the energy. We are only saying you can’t get it from burning carbon any more.

“It’s like an alcoholic who says he’ll leave the vodka in the kitchen cupboard, but first just take one little sip.”

“Developing just a little bit of the oil sands is like being a little bit pregnant. –raypierre”

This is where we disagree completely. It is actually a major assumption of yours that developing oil sands to the tune of 4 or 5 million barrels per day implies that virtually the entire resource will be developed in a ~100 year time frame. Especially when you consider that any scenario where temperature increases are limited to 2 C or less imply that a lot of fossil fuel sources must remain largely untapped. If this kind of argument applies to oil sands, why not coal?

Personally, I don’t believe that the oil sands will ever be developed at a rate much higher than 5 million barrels per day, primarily because at such a rate it won’t be possible to meet even current environmental standards, let alone the inevitable higher standards that will develop over the coming decades. That said, I don’t expect this to be a convincing argument unless you have personal knowledge of the politics and environmental regulations of Alberta, which is way too complicated an issue to cover in this forum (unfortunately).

I would agree though that one of the more effective ways (if not the most effective) to limit the growth of Oil sands development is to limit the rate at which it can be delivered to its primary consumer, the US. The strategy makes sense, even if the rhetoric is often over the top. But I’m seriously concerned that the kind of arguments used in the Keystone debate don’t bode well for the prospect of a well-informed US electorate on what will be required to keep CO2 below about 450 ppm. I wish this kind of effort could be put towards a proper price on carbon, which is far more important.

Also, its “University of Calgary” not “Calgary University” and you use the old spelling “Athabaska” at in your third last paragraph.

Good analysis. But if I read it right, you ignore accelerating feedback effects:

“This graph gives you an idea of what the Anthropocene climate looks like as . . . without even taking into account the possibility of carbon cycle feedbacks leading to a release of stored terrestrial carbon.”

Any thought on how much incorporating this bit of reality would affect your conclusion re: Keystone XL? (Or did you already incorporate it in your assumption of “a 50-50 chance that climate sensitivity is at or below this value”?)

[Response: No, unfortunately for all of us, the 50-50 chance only includes uncertainties in “fast” feedbacks like clouds and sea ice. It does include the inorganic feedback on the ocean carbon cycle (via carbonate/bicarbonate equilibrium) but not the biological carbon cycle feedback. It’s possible that terrestrial sinks could continue to sop up and sequester some anthropogenic carbon, but there’s an owful lot of near-surface carbon and if that get’s oxidized at some point in the future, then we could be in even hotter water. –raypierre]

Re: #1 Andrew Leach:

Andrew, you do indeed cover many of these points in your blog post. You cover them again in a Globe and Mail op-ed, published early last June, where, in reference to Hansen and McKibben’s claim that the Keystone “could increase CO2 concentration in the atmosphere by up to 200 ppm,” you concluded that “even if the [Keystone] pipeline is built and in service for 100 years, it’s unlikely to lead to an increase of even 1/100th of that amount.

Is it fair to say that you are in the “pipeline is no big deal camp?”

[Response: I think McKibben’s “lights the fuse” metaphor is pretty apt. The one pipeline would be no big deal if there were some agreement that that’s all the oil that’s coming out of the sands, but how likely is that? One pipeline doubles the oil flowing to US refineries, generates more market, generates more capital to develop more oil sands, then demand for more pipelines and … well you get the picture. Hard to predict the future, but it’s hardly a trivial concern. –raypierre]

#6 Steve: As an Albertan, I think Schindler is correct that we are being cheated by our government which gives the stuff away far too cheaply. But we have little chance of getting rid of our petro-state provincial government anytime soon, and our current federal government is even worse, cutting funding for environmental monitoring and implementing other stupid, destructive policies.

About the First Nations lands, though, it varies from place to place. Treaties 6 and 7 in central and southern Alberta, signed in 1876 and 1877, surrendered that land to the government of Canada. In 1887 the government first started to reserve subsurface rights from land grants in the prairie provinces, so Indian reserves which had been surveyed before then kept the subsurface rights, as did early homesteaders. Some of these First Nations have benefited a lot from the oil and gas under their lands, though there are also lawsuits against the federal government for its handling of the oil and gas money and royalties.

Treaty 8 including northern Alberta was signed in 1899, so I think the reserves there would probably not have kept the subsurface rights unless that was specified in the treaty.

Then there are the Lubicon Cree, who never signed the treaty and may have a legal claim to the land and subsurface rights. There’s a long story of failed negotiations there, but I’d say they are probably having their rights violated.

http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/cescr/docs/info-ngos/lubiconlakeindian.pdf

#5 Mark J. Fiore asked about methal hydrates. I have also read enough (including on RC!) to have the same question. It would be very helpful if raypierre added them (and any other significant forcings/feedbacks likely to occur) to the calculations. Or explain why they are not significant factors.

Oh yes, and the idea of moving water from northern Alberta to dry southern Alberta has been around for decades, but no government was insane enough to try it. If Texas needs water, Texas should build desalination plants or something, because we don’t really have that much to spare for other countries.

This is an excellent post – thanks, Raypierre!

Jim Bullis and Mike Whitfield – It was the hottest summer ever measured in North America this year in Central Texas; there were 80+ days above 100ºF. We are seeing the continuation of the worst 1-year drought in Texas history. Our major water supply, the Colorado River, is down to less than 40% of capacity, and we are dealing with stage 2 water restrictions. At 11PM at night, it was regularly still above 90ºF for most of the summer. That’s just Central Texas. I really don’t want it to get any hotter.

Is this anthropogenic global climate change (AGCC)? If it’s not, then it is exactly what the effects of AGCC will look like. But forget about the effects of AGCC for a minute.

Developing the Athabascan Tar Sands has already destroyed over 680 sq. km. of boreal forest and muskeg swamps, and polluted billions of gallons of water. It has destroyed the habitat of many species of plants and animals, particularly boreal birds. (Winter birding, which includes many boreal birds, is a multi-million dollar business here in Texas.) Tar Sands pollution has caused increased rates of cancer in native people downstream from the open pits in Northern Canada. Refining tar sands oil in Texas will increase pollution in an area that already boasts elevated levels of cancer due to years of oil refinery pollution. Unfortunately, Enbridge’s record is not good when it comes to cleaning up after a pipeline spill:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BWE0CLSueLQ&feature=related

Of course, the fact that bitumin, rather than floating, sinks in water, unlike other forms of crude oil, doesn’t help.

I went to the State Department hearing about the Keystone XL pipeline in Austin, Texas recently. The oil companies had bussed in hundreds of people to the hearing, and paid their expenses. They had arrived early in the morning. I arrived at 10:30AM, on my own time and own dime. The hearing started at noon. I didn’t get to speak until 4:30PM. Many opponents of the pipeline, who had taken the afternoon off of work to come to the hearing, didn’t get to speak at all. It was the most corrupt public hearing process I have ever witnessed, and I have attended many public hearings. I wonder why?

Why would you want to support ANY of that?

So basically, if we assume the oil and gas are too irresistibly convenient to be left in the ground, within the trillion-ton target we could hypothetically still binge on oil sands if and only if we were to quit coal cold turkey. Well, with 43% of current world emissions from fuel combustion coming from coal (2009, IEA figures), we can forget about that.

From the other side of the pond, my best wishes for the protesters and my sincere respect for Jim Hansen and others who have followed the dictates of their conscience into civil disobedience.

I have to disagree with the direction here. I think trying to block the pipeline is a silly tactic. If these materials are economically viable, then they will eventually find some other path out, and those paths might not be controlled by the US.

Restricting supply is not the answer. It just won’t be a stable solution. Restricting demand is. Anyway, humans don’t just change from one resource to another because the first resource ran out – in fact, often, the first didn’t run out. They change because the alternative is somehow better.

The key is to make the alternatives better through some sort of carbon price, however you want to implement that. If you go around assuming that every last economically-recoverable molecule of fossil fuel is burned, you’ll despair each time a new deposit is found wherever – deep sea, arctic, what have you. That isn’t a plan.

I somehow doubt the administration has the authority to do such a thing, but I’d take a different approach: approve the pipeline under the condition that the producers pay some sort of penalty for the excess carbon used in processing this stuff, compared to conventional oil. Then, separate from this deal, continue to work on the financial incentives for using carbon in general.

In response to Ray and #28. I don’t see how fast trains would allow us to stay under the current 2000W/per capita energy use even if better transportation network would cut the energy cost of an AGU round trip by half. France’s 6000W/per capita energy use is still far away from living under 2000W.

If we accept that energy use has to double or triple (just to offer comfortable life for developing nations) then all the calculation before (e.g. Socolow and Pacala’s wedges) fall apart that assumed a reduction of the current 15TW global energy use by improved energy efficiency. Jacobson and Delucchi calculated that the available solar energy over land is 6500TW. At 10% efficiency, 5% of the land should be covered by solar panels (wall-to-wall) to provide 30TW energy.

Jacobson and Delucchi assumed that the bulk of the renewable energy would come from 3.8 million 5MW wind turbine (that would be 19TW rated capacity) providing half of the global energy demand at 11.5TW (that is 28% utilization which seems to be optimistic and the number I read so far where more around 10-20% at best). Concentrated solar taking up 0.192% land (6500TW*0.192%=12.5TW solar insolation) would provide 20% of the 11.5TW (2.3TW) which assumes 18% efficiency capturing solar energy. Once you double and triple these numbers to meet more realistic energy needs and lower your expectation to more realistic efficiencies (5-10% solar and 10-20% wind), renewables become less attractive.

If we pause for a moment on the 3.8 million wind turbine, that by itself would be an enermous infrastructure. I could not find numbers how much a 5MW wind turbine weights, but I have seen 150 ton 1.5TW wind turbines. That is the equivalent of 100 passenger car so 3.8 million wind turbine weight about the same as 380 million car (compared to the 1 billion, which is on the road today including trucks). I suspect, building the necessary power lines to connect these wind turbines would double that weight.

Jacobson and Delucchi: Providing all global energy with wind, water, and solar power, Part I: Technologies, energy resources, quantities and areas of infrastructure, and materials, Energy Policy, 2011

Preventing the construction of this pipeline will not stop development of the oil sands, probably not even delay it by very much. It’s a nice symbolic gesture, but in itself it won’t accomplish much in the way of avoiding carbon emissions. It might even increase them, as the alternatives are less efficient. In the short run the pipeline would let the oil companies get better prices for their product, so they’d like you to believe it’s absolutely necessary to the continued health of their industry; but in the long run, it really isn’t.

Without the pipeline, various things might happen. The oil will get shipped by truck or by rail to the gulf coast. It will go by by truck, rail, or pipeline to the west coast to be exported to China. More of it will be sent to east-coast refineries that currently import oil by tanker. More refineries will be built in the region served by current pipelines.

That the black stuff will be left in the ground seems about the least likely outcome.

There’s a litre of rat poison on the table. If your child drinks 200 ml of it there’s a 50% chance they will die. They ask for permission to drink 1 ml of it. This has almost no chance of killing them, or even making them very sick, and it might taste nice. Do you let them?

#6:

“Oh, and actually it’s mostly lands that were given to first nations through treaties many years ago, which means the Provincial and Federal Canadian governments are also shredding their treaty obligations in the rush to hand over the exploitation rights in a massive firesale.”

The land is question was never “given to first nations”. If anything it was given by the first nations to Queen Victoria (but that’s not quite right either). The land being developed is essentially all crown land (i.e owned by the government and primarily administered by the province of Alberta). None of the oil sands mines are on reservation land.

However, Treaty 8 grants first nations the right to hunt, trap, and fish their traditional lands in perpetuity and the land in question is pretty much all traditional lands for one first nation or another. Obviously, you can’t hunt of fish in a mine.

This doesn’t mean that any mine is by definition a violation of treaty rights, but the federal and provincial governments are required to conduct meaningful consultation with first nations affected and the first nations have significant rights that can potentially be enforced by court action. Also, courts appear to be becoming more sympathetic to the first nation’s positions every year, although the process is quite slow because these cases take a long time to work their way of the chain.

It is not clear right now at what point oil sands development will cross some legal threshold into an outright treaty violation because the courts haven’t worked through all this yet. However, it’s difficult for me to imagine how this line won’t be crossed if expansion continues to develop beyond the current plans for 5 million barrels per day development levels, if not sooner.

Ray

I didn’t say that Keystone XL was no big deal. I hope it is canceled both for the worlds climate and because in the long run it will be better for the people of Alberta.

Have said, in the technology review piece and elsewhere, that Keystone is in some respects an odd choice for the environmental movement to draw a line in the sand. Cutting emissions for American coal-fired power is cheaper and would have far larger environmental side benefits. In the long run I don’t think we will succeed in getting transportation of oil by trying to stop oil production on a site-by-site basis, we are going to have to put a high price on transportation fuels that have high carbon emissions and get much more serious about driving energy innovation they can get the transportation system off carbon.

Another minor correction, my academic affiliation is Harvard not UofC I switched a few months back.

David

[Response: Thanks for the clarification, but whoevever wrote the headline on your Tech Review article didn’t seem to pick that up from your article. That reads “Controversy over a proposed oil pipeline from Alberta to Texas is sidetracking us from bigger issues,” which would seem to put you in the no-big-deal camp with regard to the pipeline itself. Thanks also for the news on your new affiliation. Sometimes it seems academics move around more than baseball players, so it’s hard to keep current. –raypierre]

As always, an excellent article. I appreciate how you are careful to show that you avoid double-counting emissions. It is a nice contrast to the “skeptics” who typically double-count the cost of avoiding emissions, while often claiming we can’t even realistically estimate them.

@20 Balazs – good point! As climate scientists we really should be making more of an effort to live the lives our data tells us we must. This was addressed in a recent article in Weather:

Making our actions consistent with our scientific predictions, Thompson, E. (2011)

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/wea.817/abstract

@raypierre (22) Would you say then that the conclusions of the National Research Council report contradict the calculations presented in Ramanathan and Feng (PNAS September 2008), which asserted that emissions up to 2005 had already resulted in a 2.4°C (1.4°C to 4.3°C) warming without aerosols. Was that paper incorrect?

[Response: I wouldn’t want to criticize my colleagues without adequate space to give the scientific justification, but aside from that you need to remember what I said about the contribution from non-CO2 radiative forcing to date (and unlike CO2, the methane radiative forcing is largely reversible, so I myself don’t count that the same way as CO2 radiative forcing). But for a more complete story on the implications of aerosol masking I’d suggest looking at the Armour and Roe GRL paper. –raypierre]

The bigger picture is that Keystone XL represents a commitment to continue burning fossil fuels indefinitely, and, in order to do so, to commit ourselves to extracting increasing amounts of increasingly destructive and polluting forms of fossil fuels. It’s that choice of direction that really means “game over” for any hope of avoiding globally catastrophic warming.

Tharanga (#47),

Great tactical advice. How about you sell Congress on carbon pricing first, and then the pipeline protesters go home and let the market sort it out?

I don’t think I’ve seen that chart before (or if I have, I certainly wasn’t paying close enough attention).

If I have your numbers aright (a dangerous assumption, granted), added to an already emitted 500 GtC,

139 GtC from oil,

100 GtC from Gas,

230 GtC from Canadian tar sands,

846 GtC from coal, bringing this fossil fuel total to circe 1,800 GtC. My question is: what are the additional contributors of carbon that could push us into the 4,000 GtC range? how would these be unleashes/avoided?

[Response: The coal number I quoted from Nehring is economically recoverable coal. In addition, there are known, or proven, deposits that are not economically recoverable at present prices. But to get numbers like 4000 or 5000 gigatonnes, you have to go into the diffuse territory called coal “resources” which amount to coal that somebody for some reason things is out there, but hasn’t yet been discovered. It turns out that the methodology for estimating coal “resources” varies widely, and in some cases is not at all geologically rigorous. It’s fair to say that any number beyond the proven reserves is, at present, speculative. Besides coal, there is also quite a lot of carbon in shale oil (a different thing from oil sands). I haven’t yet sorted out the peer reviewed literature on that, so I don’t want to quote any numbers, but shale oil is another of those unconventional petroleum deposits that need to stay in the ground if we are to avoid hitting a trillion tonnes. –raypierre]

In response to Peter Adamski’s comment above, I would say that I am in the, “pipeline is no big deal” camp – here’s why. The pipeline itself, on a life-cycle basis, will carry product with an annual contribution of 165 Mt/yr, assuming it’s all SAGD oilsands at the high-end of steam-oil ratios. Under the most generous assumptions, whereby you assume the oil transported by Keystone XL would not be either shipped elsewhere or replaced with some other source, then this represents an incremental change on the order of fractions of a percent of global emissions.

Of course, neither of the above assumptions are likely to be true, since global oil supply and demand elasticity are not zero – alternative sources (some cleaner, some not) will replace some oil not produced if you could prevent oil sands production, and some reduction will occur in total global oil demand. My personal feeling is that the best estimates of the incremental impact of KXL are in the mid-range of the State Department estimates, or the lower end of the EPA range – 10-15 Mt/yr of incremental emissions. It’s small.

The issue, as @raypierre points out, is how you view the “lighting the fuse” argument. I’ve written a little bit on this here (http://andrewleach.ca/oilsands/ny-times-story-on-keystone-xl/). I think you need to separate the causal effect from the correlation. Yes, Alberta’s oilsands expansion plans will require more pipelines, but the question is whether building Keystone XL makes those pipelines easier or harder to build and whether it enables more expansion than would otherwise occur as a result. There’s a case to be made that building on an existing right-of-way is easier than a greenfield one, but beyond that it’s hard to see how you are lighting a fuse to anything. The only way you can assume that is if you believe there will somehow be a meaningful effect on the physical access to oil or a meaningful discount offered to the US below world prices on Canadian oil supply. We’re nice, but not that nice. Here’s a little more on that: http://andrewleach.ca/oilsands/keystone-xl-and-us-energy-security-you-cant-have-it-both-ways/

Finally, and this I think is the crucial point, is that you can’t treat blocking KXL as a proxy for climate policy even if you believe that KXL would not be viable under an appropriate global carbon policy. It would do you all well to keep in mind that the reason we have oilsands development in the first place is that there is a shortage of supply of cheap, easy, conventional oil. Limiting the supply of less easy, more expensive, unconventional oil doesn’t drive people to low carbon alternatives in and of itself – it drives them to the next best substitute with no carbon-based preferences. On the merit order of substitutes for oilsands, the next best things are generally comparable (GTL) or higher (CTL) carbon emissions per barrel of oil. I’m 100% in agreement with David Keith’s point above – if you are going to draw a line in the sand, draw it around emissions which are easily reduced at lowest cost, and for which the next best alternatives are ALL lower carbon. Coal power meets all of those criteria.

Andrew

Follow up:

Your quote on mapping resources to reserves takes some figures out of context. You quote a paper from the National Petroleum Council which, “estimates that Steam Assisted Gravity Drainage could recover up to 70% of oil-in-place at a cost of below $20 per barrel.” That’s absolutely true on an individual project, but not at all true over the entire resource base. Recovery rates of original oil in place for mining operations are much higher than 70%, but these recovery rates can’t be extended over the entire resource base – hence why much of the resource base is not included in reserve numbers. There are certainly techniques in development which could dramatically increase recoverable reserves, including electro-thermal extraction which accesses deposits too deep to mine but to shallow for SAGD, deploying SAGD in carbonate resources, etc. Reserves will certainly increase with technology, but scaling up reserves to anywhere near 70% of 1.7 trillion barrels with SAGD is not on the horizon.

[Response: The point of that quote was not to say that all 1.7 trillion barrels should be added to economically recoverable reserves right now, but to just point out the pace of extraction technology, so taking the stance that they’ll never be able to get all that oil out anyway is not a very sound position. The first oil drillers probably never envisioned secondary, let alone tertiary recovery methods. –raypierre]