Climate risk scores on real estate listings are having an impact on prices and realtors are complaining. But who should pay for these losses?

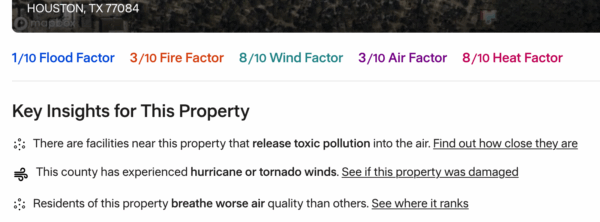

If you have been browsing Zillow or Redfin in recent years, you may have noticed that (in the US at least), listings have been accompanied by a property risk score for fire, flood, air quality, etc. These scores have mostly been generated by First Street – a private company that takes publically available information about climate risk, and downscales it to the lot level using a proprietary algorithm.

Here’s an example for a home in Houston, Texas:

Since this has been common, analysts have noticed that the worst-ranked homes for risk are suffering from relative price declines, particularly for homes at risk of flooding. This seems like a natural outcome, the higher the risk of flooding, the more expensive insurance will be, and if you can’t get insurance, the higher the risk of financial loss, and thus there is a reduction of price to compensate. If this was a static situation, then ideally these additional costs/risks would have been built into the historical prices and new prices wouldn’t be any worse affected. However, the situation is not static.

Intense rain events, wild fires, coastal flooding etc. are becoming more common in many places (while air quality issues are decreasing), and so risks to properties are changing over time, and homeowners are finding that they may not be able to sell their home for as much as they expected. That is a (relative) loss to those owners, for something that is not their fault (at least directly). Additionally, lower (relative) prices mean lower (relative) real estate commissions, and thus this has upset the realtor industry as well.

This is actually a big problem

Sympathy for brokers is not high outside of the industry (to say the least), and their struggles are not going to win many hearts or minds, but the bigger issue is much more serious. Climate changes are going to lead to increased future losses not just because of more ‘stuff’ being built (a big factor in increasing historical damages), but also because existing properties are facing more risk.

For example, take a row of houses along the North Carolina dunes, one of which fell into the sea this summer. Sea level there is rising (even more than the global mean), predominantly as a function of human impacts on the climate. Thus, a home built in 1976 that Zillow values at over $400,000 is now actually not worth anything. There are many less extreme examples where rainfall intensity increases are leading to more risks of flooding, or increases in fire weather etc. but the point is that areas of higher hazards are expanding and, objectively, many property values are (relatively) decreasing.

Generally speaking, property value rises and falls are felt by the current owners – they benefit (when they sell) if an area becomes more desirable, or take a loss if the opposite occurs. Public policy can impact this, but mostly society deals with this via changes in property taxes and assessments (in the US at least). The impacts due to climate changes are different though – these are changes that can in fact be blamed on our historical emissions that we have known for decades have been having such an effect.

Previously, it was a situation like pass-the-parcel – whoever was left holding the property when the impact was felt (the flood, the fire, the collapse into the sea) would end up paying for it or, at best, split the losses with their insurance company. The risk factor information is helping spread the costs to the current owners (as well as the future owners), which (I think) is a bit fairer but, of course, the costs are not being borne by the people causing the issue (the fossil fuel companies, the people that used their products etc.). People have also argued that society writ large should cover these losses – that regional or federal governments either through grants or insurance payouts should compensate owners, while others argue that the oil and gas companies should pay.

There is a real issue in how reliable these risk assessments are – if they are wildly different from different companies or approaches, or if the algorithms are proprietary, then it’s possible the impacts from releasing this information will be sub-optimal. But both Florida (h/t Kelly Hereid) (for hurricane damage) and California (wildfires) are leading the way in having public, open source, catastrophe models, and conceivably that could be spread more widely.

In practice, there is going to be a patchwork of different ideas, and different models, but there is no (sensible) answer that is based on ignoring the risks to keep prices artificially high. Even realtors should be able to accept that, and if they want to be compensated for their loss of commissions, they should get in line to sue the people who caused it.

References

- C.W. Callahan, and J.S. Mankin, "Carbon majors and the scientific case for climate liability", Nature, vol. 640, pp. 893-901, 2025. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08751-3

I am surprised that the realtor industry as a whole is upset about this. Based on econ 101, there’s a demand for housing, and a supply of housing. If some of the housing is devalued, that will make the demand for the remaining housing greater, so I would expect that the net effect on realtors as a whole would be a wash.

(obviously, the impact on the individual homeowners and realtors with the devalued housing will lose out, but homeowners and realtors representing safer housing will win)

(this also doesn’t address the question of whether the information is accurate)

” Sympathy for brokers is not high outside of the industry (to say the least), and their struggles are not going to win many hearts or minds,”

Real estate agents: busy raising housing prices the world over to their absolute maximum (what the market can’t bear) so that not only are average locals barely able to afford to buy a home there anymore, let alone even rent one, but soon as they make community housing expensive all the other costs in living in the area increase to. The result is that the poor are driven out and increasingly into ghettos, making subsistence wages, or homelessness … or death. In this way it’s becoming a rich only world. Is that intentional?

Don’t get me wrong, this is not a typical political call to spread crummy urbanization with its broken sidewalks, and potholed streets, abundant litter and chain link fences, ubiquitous graffiti and blasting car stereos around. It’s call to say to agents, c’mon, enough is enough. Enough with the greed. Maybe if you become fair everyone can live and both ghettos and mcmansions will become a thing of the past.

I don’t think realtors set market prices to a significant degree; in my experience they try to find the sweet spot between a higher price (and thus, a higher commission) and selling in a relatively timely manner (and thus avoiding the risk of losing any commission at all.)

That’s true, they do want to sell in a timely manner, and they do have to price for higher insurance in flood and fire prone areas, but they still try to sell on the highest side they can (with that in mind). That pressure is driving prices. It’s become unlivable to be poor.

I looked at prices in Chile, an attractive area because it’s coastal, and found that pretty much the entire country is now priced to be unaffordable to native Chileans. They cater to rich American expats. According to one realtor I talked to there he it’s gotten very expensive in Chile.

https://deficitcero.cl/en/blog/current-state-of-middle-class-sectors-regarding-housing-access-in-chile

Maybe things will moderate out in some way but right now the only way some people can buy, rent or even survive is if wages also rise… or they move. Don’t like exporting American greed to other countries.

By the way, this also applies to other countries. Slowly prices are all rising to their maximum affordability, though I did find Indonesia still mostly affordable to native Indonesians.

This is just one example of the more general problem: that *the system of market pricing can’t register the real costs of using fossil fuels, since most of those costs first show up a long time after the fuels have been consumed/burned*.

This demonstrates that *we as a society have to put a political price on fossil fuels*. This again has to be done both

1) as scientifically as possible – meaning based on a scientific calculation of the future societal costs of using different types of fossil energy sources, i.e. based on their respective output of CO2, methane etc. when they are burned and

2) as social just as possible, meaning that everyone must pay according to their relative part in the production and usage of fossil fuels.

The simplest and most unbureaucratic answer to this is James Hansen’s proposal for a *carbon fee and dividend*. Thereby there is put a – yearly rising – fee on all fossil fuel at their point of entry onto the national market (the oil well, the harbour, the pipeline etc.) and according to their respective carbon content. The revenue from this fee isn’t included into the Treasury, but instead repaid as a equally divided dividend to each and every citizen. Each citizen receives exact the same amount of money each year as his or her (etc.) dividend. According to economic calculations, this will mean that in general the people who consume most fossil fuels (live most carbon intensive) pay most of the fee. This again will have the effect that fossil fuels are gradually being priced out of the market, because they rise in price relative to renewables. Which is exactly what we need to transit away from the fossil fuel economy.

Why is there such enormous resistance to this proposal? You don’t have to be Sherlock Holmes to answer that one. Statistics from among others Oxfam give you the answer: the richer you are today, the more fossil fuels you consume. In general. The fossil fuel consumption of the oligarchs and the other ruling class members in the US, Russia etc. is, has been enormous and is still growing. Their ideology – which you could call “the (more and more!) unenlightened (you could even say: stupid) rule of the moneyed classes” is the one and huge obstacle to solving this rather simple and indeed now very burning (!) social problem. Of course there are some rather rare and special exceptions to this general rule, fx. (small) farmers and truck drivers, who will have to be compensated, but this problem is easy to solve, *if you want to*, but “unfortunately” and “accidentally” our completely dominating political class members show very little interest in this… In today’s global oligarchy with all it’s wars for oil etc., this is no deep mystery, but it’s unfortunately just the old one with homo sapiens, which the norwegian author Ingjald Nissen in a once (in Norway the years after 1945…) rather famous book called “The dictatorship of the psychopaths”, see fx. https://www.adlerpedia.org/bibliographies/psychopatenes-diktatur-the-dictatorship-of-psychopaths/ and https://dbpedia.org/page/Ingjald_Nissen ), (which is of course a simplification of deep historical and anthropological problems, which you maybe could summon under the name “the Caligulan problem”, but nonetheless, given today’s again overwhelmingly ruling personality types – Trump, Putin, Netanyahu, Musk, Thiel, Larry Ellison, Bezos, Bill Gates, russian oligarchs, Bin Salman, Xi Jinping etc. etc. etc. … – a very urgent one, to say the least).

You make a very persuasive case, both for Hansen’s version of a carbon tax, and for Nissen’s argument about fossil fuels being indirectly the driver of today’s move towards the Caligulan situation. I must read that book.

Karsten…”This again will have the effect that fossil fuels are gradually being priced out of the market, because they rise in price relative to renewables. Which is exactly what we need to transit away from the fossil fuel economy..”

So.. what will be the costs to everyone for all of the transportation involved in the transition to renewables and EVs? After all FFVs will be doing all of this work. At least until the transition is close to completion..

Will you please stop lying. EVs already do some industrial transportation work. I posted sources on that. They will almost certainly do very significant amounts well before the transition is complete.

Yes… and during that time more CO2 will be added. After all there are eight billion people that need to be fed. EVs are not doing that. You can’t get away from using FFVs to phase out fossil fuels during the transition.

“You can’t get away from using FFVs to phase out fossil fuels during the transition.”

Trivially true.

“After all FFVs will be doing all of this work. At least until the transition is close to completion.”.

Trivially false.

The extra accumulation of CO2 from burning fossil fuels is much lower over the lifetime of the transition compared to over the same timeframe with no transition, therefore, logic dictates that if reducing CO2 emissions is the goal, transitioning from FFVs to EVs is the optimal decision because the less extra CO2 in the atmosphere, the better. Just because it is impossible to stop all emissions overnight does not mean it is pointless to do it over a transition period, in the same way that because it is impossible to go from being fat and unfit to muscular and strong overnight, engaging in a physical training plan and improved diet to get there over a period of months is still a good thing to do.

KT: You can’t get away from using FFVs to phase out fossil fuels during the transition.

BPL: Less and less the more renewable capacity is added.

Adam Lea, well said.

OMG, don’t you ever stop harping on this?

The lifetime cost of ownership is already usually less for EVs, and the upfront cost differential is shrinking:

https://insideevs.com/news/748568/price-gap-evs-ice-shrinking/

And now, one new vehicle sold globally in 5 is an EV:

https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2025/trends-in-electric-car-markets-2

KT: what will be the costs to everyone for all of the transportation involved in the transition to renewables and EVs? After all FFVs will be doing all of this work.

BPL: Increasingly not true.

Yes… but in the long process to make the transition gasolines and renewable biofuels will be adding more CO2 to the atmosphere. There is no way around it,

KT: in the long process to make the transition gasolines and renewable biofuels will be adding more CO2 to the atmosphere. There is no way around it,

BPL: True but irrelevant. The amount they’re adding will steadily decrease.

Ken Towe; “FFVs will be doing all of this work. ”

I.e. “FF good, non-FFs bad! FF good, non-FFs bad! FF good, non-FFs bad! Baaa, baaa!.”

But.. all of us have enjoyed the high standards of living these “bad” fuels have provided. Now some enlightened people wan’t to remove them because the exhaust by-products are CO2 and water vapor.

No, ALL enlightened people want to remove them.

Ken Towe: ” But.. all of us have enjoyed the high standards of living ”

Stop living in the past, Mr. Towe. It’s NOT 1825, nor even 1925. The path to affluence

that has worked for a few 100 mln people, does NOT scale up to the world of 8 billion.

The white countries + some SEAsia + Middle East got rich on dumping their waste for free into atmosphere – thus reaping the profits, while passing the costs of their excessive consumption onto others – the rest of the world and onto the future generations, to whom we leave the greatly impoverished ecologically world, stripped of the easy to extract resources, and with damaged, unstable and in some places soon unsurvivable climate,.

This is neither fair nor sustainable – the rich countries have already filled the atmosphere with enough of GHGs that there is HARDY ANY ROOM for NEW emissions from the rich countries, MUCH LESS so if the developing countries say – we want what you have.got at our expense.

So get your head out of your rectum and stop defending the FF state-industrial complex, bent on milking the FF profit cow for everything it has. Stop supporting Russia’s war on Ukraine, Iran, Qatar and Saudi Arabia’s support of terrorism, and UAE financing the genocide in Sudan – they could NOT do it without people like you, Mr. Towe, people who to maintain THEIR “high living standards” are OK with financing even the most inhumane atrocities against the others. MAGA mentality – “me, my consumption now, and screw you!”

We have enjoyed the high standards of living that cheap energy has provided. That cheap energy has so far mostly been provided by burning fossil fuels. There is no physical reasoning why that energy has to come from fossil fuels, when people use electricity in their homes, how it was generated is irrelevant to them. Since burning fossil fuels over a long period of time has been demonstrated to a high probability to be leading to nasty side effects, moving to another cheap energy source which doesn’t have the nasty side effects is the logical thing to do. Renewable energy is as affordable as energy from fossil fuels now despite what those with vested interests want to claim. If you have an illness and the doctor prescribes a drug which eases the symptoms but causes unpleasant side effects, do you choose to live with the side effects no matter how unpleasant they are, or do you go back to the doctor and ask if they can prescribe an alternative drug?

KT: all of us have enjoyed the high standards of living these “bad” fuels have provided. Now some enlightened people wan’t to remove them because the exhaust by-products are CO2 and water vapor.

BPL: No, they want to replace them because the CO2 causes global warming, which will collapse our civilization if allowed to increase without limit.

I hope that the real estate insurance companies are compiling actuarial statistics for each region for fire, floods, hurricanes, etc. The risk score for each climate risk should be computed from these statistics. Then the scores could be the same for all real estate companies.

Oh, they sure are:

https://www.npr.org/2025/11/12/nx-s1-5546754/climate-home-insurance-cop30-prices-expensive-disasters

Whether they choose to be transparent with that information is another question, of course.

Zillow Removes Climate Risk Scores From Home Listings. The scores aimed to predict a property’s risk from fires, floods and storms, but some in the real estate industry as well as homeowners have called them inaccurate. – https://www.nytimes.com/2025/11/30/climate/zillow-climate-risk-scores-homes.html

paywall free link: https://archive.ph/KQAbZ

In 1992, EPA researcher James Titus published a paper mapping potential impacts of climate change on the US. He also estimated remediation impacts, which were surprisingly reasonable.

His work would be a valuable addition to discussion of these issues: https://research.fit.edu/media/site-specific/researchfitedu/coast-climate-adaptation-library/united-states/national/us—epa-reports/Titus.-1992.-US-Cost-of-Climate-Change.pdf

“On the Move” is a must-read account of U.S. climate migration. This timely book by Abrahm Lustgarten argues that mass migration triggered by climate change will fundamentally rock U.S. society.

https://yaleclimateconnections.org/2024/04/book-review-on-the-move-is-a-must-read-account-of-u-s-climate-migration/

Abrahm Lustgarten has done outstanding work; the earliest I know of is ProPublica on the Colorado River and water problems in the southwest:

Killing the Colorado: The Water Crisis in the West – “The Colorado River is dying — the victim of legally sanctioned overuse, the relentless forces of urban growth, willful ignorance among policymakers and a misplaced confidence in human ingenuity. ProPublica investigates the policies that are putting this precious resource in peril”

https://www.propublica.org/series/killing-the-colorado

Who should pay when a second home is built on a site chosen for its exclusivity and view. My home in Vermont is surrounded by ski slopes with many overly tricked-out home at the slopes and the surround area. One near me just now being completed is a huge thing atop a mountain. The paved driveway has several switch-backs (yet to be tested through a full and awful winter) which I know will be a dangerous one to keep clear of snow. Not only that, I think we are having more winter precip as rain to ice. And that is nearly impossible to conquer.

So, here is a house built without regard to anything…cost does not seem to be a consideration. Who pays for that should diesel fuel become unavailable and the foolish driveway simply cannot be cleared… possibly a team of Mesoamerican laborers with shovels.

Any compensation should factor in this tremendous disparity between what is appropriate and disgusting largess.

Who should pay for the social cost of carbon? In the normative sense, IMHO everyone should pay in proportion to the amount of fossil carbon they’re each responsible for transferring to the atmosphere. Carbon capitalists, i.e. fossil fuel producers and investors, might be assessed all the profit they’ve made by socializing climate-change out of their production costs. Consumers might pay in proportion to how much of the stuff they’ve burned, or caused to be burned, to make all the goods and services they’ve bought on the global market. A proxy, e.g. lifetime income relative to their country’s average, might work as well.

How about the victims of climate change to date? Many of them have consumed little fossil carbon themselves, but paid with their homes, livelihoods and lives for wealthier consumers’ socialized climate change costs. Should they have? I’m reasonably confident the non-sociopathic among us would agree they shouldn’t. I can’t say it better than Jerry Taylor did (https://theintercept.com/2017/04/28/how-a-professional-climate-change-denier-discovered-the-lies-and-decided-to-fight-for-science/):

Jon [Adler, Competitive Enterprise Institute] wrote a very interesting paper in which he argued that even if the skeptic narratives are correct, the old narratives I was telling wasn’t an argument against climate action. Just because the costs and the benefits are more or less going to be a wash, he said, that doesn’t mean that the losers in climate change are just going to have to suck it up so Exxon and Koch Industries can make a good chunk of money.

In the purely predictive sense, however, the cumulative SCC should rise as long as atmospheric CO2 does, and carbon capitalists shouldn’t be left with stranded assets. The “Matthew effect” obtains (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matthew_effect). It’s why AGW is a political problem.

Hell, even I don’t want to pay climate reparations for my middle class life! I’d settle for collectively decarbonizing the US and global economies so that the total cumulative SCC is capped, even if my living expenses increase modestly and temporarily! Y’all make of that what you will.

Mal Adapted said: “IMHO everyone should pay in proportion to the amount of fossil carbon they’re each responsible for transferring to the atmosphere…… Consumers might pay in proportion to how much of the stuff they’ve burned, or caused to be burned, to make all the goods and services they’ve bought on the global market. A proxy, e.g. lifetime income relative to their country’s average, might work as well.”

Nice ideally and in theory, but impractical in reality: Evaluating millions of consumers individual use of fossil fuels would be an incredibly difficult, bureaucratic and expensive task, and virtually impossible to do with any accuracy. Using their income as a proxy is problematic. While high income people tend to use more fossil fuels, a very significant number have made significant efforts to reduce their emissions, buy electric cars, etcetera. It would be totally unjustified to punish them with costs. And a bureaucratic nightmare to identify these individuals and exempt them.

And I would suggest a government policy that tried to make its citizens pay for their emissions, and as a way of compensating people who bought homes in at risk areas would be incredibly unpopular and a guaranteed election loser so it is unlikely to be adopted. (I am aware you said “ideally’ so you have probably considered these issues).

I do normally tend to agree with what you post on how we best mitigate the climate problem in a technical and political and economic sense. There is a need to put a price on carbon and I think there is a need to have a policy like a carbon tax and dividend, but primarily as a way to push change ,and assist low income people make changes. I’m not sure it should be a mechanism for compensating people for harms caused by emissions. It cant be all things to all people, or it will end up doing nothing and would face huge opposition.

Of course, if a tax/fee system were implemented, it would tend to be as fair as the market would be… etc. ( https://scienceopinionsfunandotherthings.wordpress.com/2023/08/14/why-a-net-co2eq-tax-makes-sense-or-at-least-it-did-and-also-why-it-may-not-be-enough/ ) As far as past emissions are concerned,

There’s a concept/principle in tort law I learned about in High School: “Deep Pockets” – as I recall, when a group of parties share responsibility for damages, if some can’t pay, those that can, do. It’s not fair, as costs should ideally be apportioned by degree of (moral/ethical) responsibility (not necessarily the same as causal responsibility – but that’s not the point here) – but it works. And I’m reminded of a couple of lines in a Hallmark TV Christmas movie which went something like this [spoiler alert]:

~“But that wouldn’t be fair”

~“What about any of this is fair?”

How did the deep pockets get deep? Yes, some people may work harder, may make smarter decisions, may invest strategically in themselves, etc. (but it’s worth considering why those who didn’t/don’t do so didn’t/don’t.) … and have good ideas – which, given the nature of ideas, will tend to involve some luck (?) although the ideas themselves should be rewarded, of course, via their implementation. But anyway, how could someone work so hard, so effectively, as to actually earn billions of dollars? If we imagine an inventor or innovator who manages to drastically grow total wealth, then if they are simply taking a share of that wealth, assuming everyong else is also benifiting …? But I have come to realize that eg. Elon Musk is perhaps not so much like a Tony Stark nor a Lex Luthor but perhaps more like … um… some guy who won a lottery? Idk, I haven’t read enough, this is just a vague impression I’ve gotten. The point is, I think there’s reason to be skeptical of the super rich having truly earned their economic status. Some are better than others, but… (TBC)

“(but it’s worth considering why those who didn’t/don’t do so didn’t/don’t.)” – of course, there is the matter of working harder, smarter, etc., for less, or just to exist (eg. medical and mental health issues, poverty/opportunity/war etc. – the tallest plants get the most sun, and so on – need $ to make $ – see also :

Veritasium:

“You’ve (Likely) Been Playing The Game of Life Wrong” –https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HBluLfX2F_k

“The Strange Math That Predicts (Almost) Anything” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KZeIEiBrT_w

“Why It Was Almost Impossible to Make the Blue LED” (now that guy worked HARD!) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AF8d72mA41M

—

“Tax is not theft: why the “it’s my money” argument is wrong” Richard J Murphy https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SK-PmfkViDE&t=2s (the beginning part covers things I’d already thought of – basically, people generally ‘make money’ (earn income/wealth) with some public input and unless living as a hermit, dependent on others (employees/employers/suppliers/customers/teachers/trainers/infrastructure builders and maintainers…etc.) Then there’s some other parts I hadn’t thought of, and a few points I’m not sure about… I’d quibble about the existence of the market (as I do with capitalism); in a sense a natural ecosystem or a group of friends or maybe even a single brain is a market (ideas, time, food, choices are made … etc. … I’m not counting $ as necessary)…

“This Christian Belief Shapes Every Republican Policy” Jezebel Vibes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OTFdN87rpk8

…

‘“The Strange Math That Predicts (Almost) Anything””

Interesting, but more like using probability math to point to a likely answer.

‘“Why It Was Almost Impossible to Make the Blue LED””

Because that bandgap of common semiconductor materials didn’t match and they had to engineer compound materials. Took a couple of years, working commercially by 1994. Contrast to the difficulty of creating optoelectronic materials directly on silicon substrates. I did early work with germanium+tin to create direct band gap IR. Now, 35 years later, still making only incremental progress. Blue LED was easy by comparison because of the direct band gap materials available to create monolithic devices.

I am on a much more easy crusade now — figuring out ENSO, QBO … lol

So what I’m thinking:

Aside from anthro-GHGs themselves, there’s a lot of damages from the MAGA administration that will have to be paid/compenated (well, no, but they should be! Eg. immigrants and any others who’ve suffered damages from ICE (including theft) – all those immigrants who were here legally or at least going through the legal process should be allowed to return and jump to the head of the line (which should be widened), with travel and legal expenses paid. Rebuilding Gaza (to be fair, not entirely on this administration). Whatever losses that offshore wind company incurred… … … … … ), and I’m not sure there’s a legal way to just take billions of $ out of the Heritage Foundation specifically. We (in the U.S.) should raise taxes. On the rich. Maybe the upper middle class, too. But especially the rich. (I would have all of Musk’s assets seized if I could. Is there enough jail space for ICE-gestapo?) Maybe with credits to those who have solar roofs, and have an EV – no, to those who don’t have an ICE-car (because why reward people for having more cars?…) But also, of course, stop all fossil fuel subsidies (*I’m referring to actual public expenditures, not the unaccounted externalities – but yeah, tax/fee that, too).

PS – “Carbon Offsets Haven’t Delivered. Is It Even Possible to Fix Them?” Engineering with Rosie https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zLJyvq-FxMk :

CDMs seem like a good idea, but they should give developed nations a chance to make up for past emissions, not present ones.

“Climate risk scores on real estate listings are having an impact on prices and realtors are complaining. But who should pay for these losses?”

Nobody should be paying for peoples losses. People have known about the climate problem for a couple of decades, and still choose to live in high risk areas, despite knowing the risks. Caveat Emptor: buyer beware. The losses are their problem. Its obvious what areas are high risk: Living on floodplains, very close to sea level, in a forest,

In reality some low income people might be left destitute, so governments will probably provide some limited help to people in exceptional circumstances, which is fine. But I cant see governments providing anything beyond that. They don’t have the money.

People don’t necessarily choose to live in high risk areas, even in wealthy countries, high inequality means there are people at the lower end of the income distribution that live in a high risk area because that is the only housing they can afford, and they have to live somewhere. People live in mobile homes in Florida despite the fact they will be destroyed in a major hurricane because they are cheap. It is even more stark in poorer countries, where in order to support their families, people make an income from the ocean, and to do that they have to live along coastlines vulnerable to violent tropical cyclones. Those of us who have comfortable lives and plenty of life choices thanks to a good income should be careful not to demonise the destitute for making choices that would be choices to us, but may be the only option for them.

Adam Lea, yes I concede some people in places like America have no real choice but to live in high risk areas. However I would suggest they would be in a minority and would generally be low income people. I have no problem with governments helping low income people as stated.

Yes, and proximity to work is another factor. There is a difference between working class people who have to pick from what’s available within an area and rich people building mansions on the Gulf Coast.

All properties have plusses and minuses. It has always been that way and always will be. If you buy in a forest, a forest fire could burn your house down. If you buy in much of the US, a tornado could blow your house down – same with hurricanes along the coasts. In the far north, if your home is built on permafrost and it melts, it could have a catastrophic structural failure – has been happening long before any significant warming because of poor design that allows heat from the home to transfer to the permafrost. A home in a crime-infested area, will be less desirable. A home next to a busy street will be less desirable. A home in a high-tax state will be less desirable. A home in an area with crappy weather will be less desirable and on and on

This topic is a non-issue. Next.

Do you really not grasp that there is a big difference between more or less static risks to individual homes, and steadily increasing risks to homes across large regions? I would have thought that that wasn’t so conceptually challenging!

Add it to the long, long list of things Mr. KIA doesn’t understand

Time is too short to track all that!

Yes but these things are happening more than they otherwise would be. That’s kind of the whole point.

Mr. KiA, you give your game away with your closing remark, “This topic is a non-issue. Next.”

Only three types of individuals would close with such a inexact, incomplete declaration:

1. Those invested in keeping finance systems as is and damn reality, and/or

2. Those interested in maintaining political status quo and damn reality.

And the other,

3. Those so poorly informed or otherwise impervious that they are easy prey for folks who align with one or both the prior two.

The implications as evidenced by what is already unfolding (let alone what will come to pass), even just in the one slice of business and finance Gavin’s post explores a small bit, are profound. For everyone.

From the referenced NATURE article … “Will it ever be possible to sue anyone for damaging the climate? Twenty years after this question was first posed, we argue that the scientific case for climate liability is closed. Here we detail the scientific and legal implications of an ‘end-to-end’ attribution that links fossil fuel producers to specific damages from warming.”

Has everyone forgotten that without the energy from the fossil fuel producers all of us would be living in the dark ages? Our lifestyles and high standards of living are directly related to the use of fossil fuels for energy.. That’s why atmospheric CO2 is making new records every year.

So are those wanting to sue someone for damaging the climate actually suing themselves for damaging all economies by recommending urgent reductions in emissions?

And without horse shoes, nobody could travel…

And without oil from whale blubber, nobody could light their houses

Do you ever get tired of flogging the hell out of the same poor old straw man, Ken?

Maybe it’s time to build the energy economy for the 21st century and beyond rather than sticking with that of the 19th century….

Come on Ray.. get back into the real world.. There are no EVs making the transition to renewables possible. FFVs are doing all the work to build the new energy economy.. Delivering food and all of the materials needed. Reducing emissions will make it even harder and more costly. And none of the CO2 already added will be taken out. These are not “straw men”. Ray.

Ken Towe @ 4 Dec 2025 at 9:31 AM

KT: “There are no EVs making the transition to renewables possible. FFVs are doing all the work to build the new energy economy.. Delivering food and all of the materials needed. Reducing emissions will make it even harder and more costly”

Nigelj: You’re wrong. I previously gave you examples that EVs are already doing some of the work of building renewables, delivering materials, and delivering food. It is a small amount at this stage but I only need one single example of a small contribution to show you are wrong. You even acknowledged EVs are doing some work and that I gave you examples as below:

Nigelj @ 1 Dec 2025 at 6:29 PM : Will you please stop lying. EVs already do some industrial transportation work. I posted sources on that. They will almost certainly do very significant amounts well before the transition is complete.

Ken Towe replied to me @ 4 Dec 2025 at 9:40 AM: Yes… and during that time more CO2 will be added.

So you have just given two completely contradictory responses to me and Ray Ladbury, Either you are lying or you’re incredibly confused and don’t know what you type.

You’re definitely a propagandist, that takes every opportunity to repeat your propaganda regardless of the topic of the article. If the article was on Taylor Swift Ken Towe would sneak in a comment on needing fossil fuels.

Must be time for an update on heavy-duty EVs:

https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2025/trends-in-heavy-duty-electric-vehicles

TLDR?

–Global electric bus sales exceeded 70,000 units last year, and were up 30% yoy.

–Medium and heavy EV truck sales exceeded 90,000 units last year, with a yoy increase of about 80%.

Still a fraction of the totoal fleet, of course, except in certain regions. (E.g., Oakland, CA, now has an all-electric school bus fleet; Hebei province, China has over 30,000 EV trucks on the road.) But growth continues to be robust, battery costs continue to fall, charging infrastructure continues to improve, and the use cases continue to expand rapidly.

KT: There are no EVs making the transition to renewables possible. FFVs are doing all the work to build the new energy economy..

BPL: I am a one-note man/I play it all I can.

I could 5 posts by KT so far in this thread, all repeating the same point endlessly.

Wrong, Kenny. We just bought an EV. Maybe you should be using a calendar where the first 2 digits in the year are “20” rather than “19”.

KT: FFVs are doing all the work to build the new energy economy.

BPL: A larger and larger percentage is renewable. So stop with the party line already.

OK Johnny, play that one note loud, no mojo,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RWlxR2-wBus&list=RDRWlxR2-wBus&start_radio=1

My take: https://scienceopinionsfunandotherthings.wordpress.com/2023/08/14/why-a-net-co2eq-tax-makes-sense-or-at-least-it-did-and-also-why-it-may-not-be-enough/

Additional to Nigelj’s, Kevin McKinney’s, & Barton Paul Levenson’s points,

To the extent that fossil fuels/etc.* are used, I expect the price signal will propagate along the supply chain (up and down, ie if the tax/fee were applied at the power plant, the power plant wouldn’t be willing to pay as much for the coal, so the mines would take a hit on their profits, etc.; I prefer to tax at the mine/well – it just seems easier to me) – profits would go down and/or price rises would be passed on, etc.

So clean energy and associated infrastructure would be more expensive, but consider the EROEI, the CO2eq kg/kWh(e), etc. – what is the impact in providing otherwise clean energy compared to fossil fuel energy use to provide energy directly?

( https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/en/publications/studies/photovoltaics-report.html p.39/56:

“Energy Payback Time of Silicon PV Rooftop Systems

Comparison of EPBT China / EU, Local Irradiation and Grid Efficiency in 2021”

Look at how small the contribution of transportation is to the total EPBT (~ 0.01 to ~0.02 yrs) – okay, granted this is rooftop PV and doesn’t include batteries(/PHS/graphite thermal etc. AFAIK, transmission upgrades AFAIK, etc., but still…)

*also, cement, deforestation/etc., beef, cheese & rice, landfills and fugitive CH4, etc. And other pollution issues – mines H2SO4, U, Hg, and so forth. Not all are amenable to the tax/fee approach (tax/fee approach doesn’t make sense for some things eg. animal welfare, child labor etc.) but proper regulation in whatever form (requiring mining companies clean up after themselves?) would either directly or indirectly inject price signals… etc.

Oops! That comment was supposed to go here: https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2025/11/who-should-pay/#comment-842531, in re Ken Towe

But also,

With the dividend, people can afford the higher price, but the incentive is now to get the lower CO2eq-embodied product/service. And on with the transition.

Although that may only be post-manufacturing transportation(?)

Well said. The things liberals claim to hate are the things that make their lives possible and comfortable: capitalism, fossil fuels, the US Constitution, and the other characteristics of WESTERN CIVILIZED NATIONS, etc,. They would not even consider living under the conditions they claim to admire every single day. Give thanks to the men and women who work hard making affordable, reliable, and abundant energy available to the entire world: https://www.youtube.com/shorts/Ch94OO6WXFU

For those who don’t want to use FFs, go to backwoodssolar.com or any of a thousand other companies and buy a solar and/or wind system, or have your local RE company design and install one for you. NOTHING is stopping you from doing so. Start by selecting appliances designed for your system, so the system can be as small and energy efficient as possible to save you $$.

KIA: Well said. The things liberals claim to hate are the things that make their lives possible and comfortable: capitalism, fossil fuels, the US Constitution, and the other characteristics of WESTERN CIVILIZED NATIONS, etc,.

BPL: That’s a damned lie. On capitalism, you have liberals confused with Marxists; they are not even remotely the same thing. On fossil fuels, renewables are now cheaper, and we hate fossil fuels because they’re undermining civilization. We love the constitution more than the conservatives who are right now running roughshod over it. So take your lies and shove ’em.

The thing is, as I see it, there is a significant subset of people who don’t give a damn about externalised costs as long as they are out-of-sight-out-of-mind and they are benefitting. Much of climate change and its potential consequences is not about the science, it is about values. Capitalism in its current form encourages this though not including things like human suffering on the balance sheet. I reckon a large contribution to the solution is for all costs to be internalised in terms of a monetary equivalent on the price of products, somewhat analagous to the legal situation where if you cause harm to someone through carelessness/negligence, you will likely have to pay compensation to the victim(s). If you want people to eat less meat due to the carbon footprint, insist that anyone who wants to eat meat must directly slaughter the animals themselves with their own hands, rather than paying someone else to do it out of sight out of mind, I would bet a large sum of money that a lot more people would be vegetarian in that situation.

There are some freight transportation challenges remaining… (which is how much of global energy?)

Engineering with Rosie:

“The Green Shipping Fuel Everyone’s Betting On (But Might Regret)” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EqupcBoH3hQ

(But PS shipping fossil fuels is a big part (40%) of current shipping volume – see 6:22 – 6:41)

“Electric Trucks Aren’t as Simple as They Seem But This Technology Can Fix It” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PGMUMAZ7shY (saw it a few months ago, just reviewed a majority of it yesterday to refresh my memory)- so, I’m not clear on if electrification of short-haul trucking – specifically round trips under 4 hrs – is essentially a solved problem or not(?), but long-haul trucking presents challenges – which have solutions, though it’s unclear which will work out … (dynamic charging ** (yay!) – vs/&/or? major transmission upgrades to warehouses?) – but it’s interesting how cost figures into the analysis. From what I recall: Autonomous vehicles would significantly reduce costs (I’m a bit skeptical that this will happen soon or …), and then there’s faster loading/etc. and that would make stopping every 4 hours for an hour charge too expensive because now you don’t need to stop as often for as long anyway. So we bring down costs, and now we can’t raise costs because everybody’s brought down costs so now it’s not competitive…? So how would this equation change with an emissions tax/fee?

** standardization necessary – maybe we can get out ahead of that? Reminds me of the speed bumps with EV charging stations (thanks for that link, David!)

…“though it’s unclear which will work out … (dynamic charging ** (yay!) – vs/&/or? ”…

A case is made that dynamic charging is a better option, although there are two versions: overhead and built-into-the-road.

…“ major transmission upgrades to warehouses?)” – major transmission expansions to warehouses

When talking about who should pay (fossil fuel companies first for forcing society through their continual fighting of clean alternatives and continually lying about it to use their product), and the Koch Brothers, let’s not forget the entire Republican Party for gleefully enabling them.

There is a difference between people who 1.have to use it because that’s all that’s available and/or all they can afford 2. people who because of big dirty energy’s disinformation campaign over the years have innocently bought their think tank lies and 3. those who knowing the risks still choose to use it.

No, we are not all equally responsible.

True.

False.

Nobody is forcing anyone to use FFs. For example, see the thousands of homeless folks living in tents, commuting to the food bank on foot with stolen grocery cart, having no heat in the tent, etc. Everyone reading this can follow their lead and become SUPER ENVIRONMENTAL DEFENDERS!

The OUTSTANDING NEWS IS that you don’t have to be that extreme, because according to the leftist news, RE is now cheaper than FFs. If true, NOBODY who cares about AGW should be using FFs today. If they are, according to the leftist news, they are throwing away their money, and since THOSE PEOPLE know the damage FFs are doing to the planet, they are the worst offenders of all. They are knowingly spending EXTRA MONEY just for the privilege of using FFs that they know will harm the planet. Them’s some BAD PEOPLE right there!

That post is very high on shrill rhetoric and low on fact-based opinion compared to your norm. Your straw man is genuinely ridiculous.

The US news footage about food banks that I’ve seen has never shown “thousands of homeless folks . . . commuting to the food bank on foot with stolen grocery cart” (sic). If anything, I’ve several times been struck by the TV coverage showing a long queue of vehicles to demonstrate a large demand for food bank supplies. Usually a fair percentage of massive (by Australian standards) FF-powered SUV’s.

KIA: Nobody is forcing anyone to use FFs.

BPL: Wrong. Everyone who gets their electricity from a coal or natural gas plant is forced to use FFs. Everyone who buys a gasoline-powered car because EVs aren’t available in their area is forced to use FFs. Everyone who uses steel or other products which are manufactured using FFs are forced to use FFs.

KIA: see the thousands of homeless folks living in tents, commuting to the food bank on foot with stolen grocery cart, having no heat in the tent, etc. Everyone reading this can follow their lead and become SUPER ENVIRONMENTAL DEFENDERS!

BPL: Wrong. No one is advocating that. Straw man argument.

BPL,

Calling KIA’s dribbling mockery a Straw man argument, or any kind of argument for that matter, seems unnecessarily dignifying. I’d simply call it snotty troll blather, roll my eyes, and move on.

Radge, I have to concede “dribbling mockery” is better than anything I’ve ever come up with… damn, it actually meets the standard for scientifically precise language I’m always calling people out on.

And “snotty troll blather” is pretty good as well.

I guess I have to up my game, eh.

yeah, like it’s really mature and sciency dude. more please, that whatcha need dude.

” Everyone who gets their electricity from a coal or natural gas plant is forced to use FFs. Everyone who buys a gasoline-powered car because EVs aren’t available in their area is forced to use FFs. Everyone who uses steel or other products which are manufactured using FFs are forced to use FFs.”

Professor…I think you are finally beginning to understand the energy dilemma.. Because everyone in the civilized world who eats anything is forced to rely on the growth and delivery of food by vehicles that use FFs. So are all travelers who fly anywhere and then rent a FFV when EVs aren’t available. Forced to use what most people use. It’s really simple to understand. FFs are still the most used source of energy. for transportation. And they are needed to phase out FFs while phasing in EVs. Forced to use fossil fuels.

KT: “FFs are still the most used source of energy. for transportation. And they are needed to phase out FFs while phasing in EVs. Forced to use fossil fuels. ”

You are only telling half the truth. We need decreasing levels of fossil fuels over time as they are gradually replaced by other energy sources. Putting it another way as renewables increase they provide some of the work to build new renewables. This is proven by the fact that the growth of coal use has declined globally, and has reduced in absolute terms in some countries.

You’re right that it’s simple. You’re wrong that it has to be that way.

Everyone is living hypothetical land here. Where fantasy and make believe rules the day.

KT: FFs are still the most used source of energy. for transportation. And they are needed to phase out FFs while phasing in EVs. Forced to use fossil fuels.

BPL: No kidding. But they will be forced to do so less and less as more and more fossil fuel infrastructure is replaced by renewables.

KIA, if I’m the average person who’s barely scraping by and deciding whether to install solar panels on my roof or keep using FF to electrify my house what do you think I’m going to do? And likely if I’m the average person it’s not even my home because I’m renting so I don’t have the ability even if I could afford it to install solar panels.

Has there been a war on solar by electric companies and is that affecting prices. Yes.

https://www.cnbc.com/2017/09/18/attacking-rooftop-solar-energy-is-a-big-mistake-commentary.html

https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/utilities-sensing-threat-put-squeeze-on-booming-solar-roof-industry/2015/03/07/2d916f88-c1c9-11e4-ad5c-3b8ce89f1b89_story.html

https://environmentamerica.org/california/articles/stand-up-for-solar/

https://solarunitedneighbors.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Myth-of-the-Solar-Cost-Shift-FINAL.pdf

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/mar/08/oil-industry-has-sought-to-block-state-backing-for-green-tech-since-1960s

Etc.

Yes, if it were a level playing field a lot more solar would be taken up. But it’s not. Yes, of course, the cost of solar itself is cheap. Way cheaper than FF. But the initial cost (much of it because of this targeted war) and the regulatory uncertainties make it not worth it for many homeowners. So they’re thinking all this hassle vs just turning on the heater. I think I’ll just turn on the heater.

Now if we’re talking cars (a new one can be about $50,000, so that’s out for the average person) so they stick with what they have. Likely a CV. Also the convenience of fueling it at some gas station that’s you find on every corner when you’re on your way to work. Do you think it’s a level playing field?

Yeah, forced to

More and more people are food insecure as more perks and money are filtered to those who already have the most wealth and power.

Meanwhile, the administration is defunding help for those on the edge.

https://www.gbfb.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/GBFB_Food-Access-Report_2025_final.pdf

The Costs of Hunger: Food Insecurity Rates: “In 2024, more than 1 in 3 Massachusetts households—approximately 2 million adults—reported food insecurity at some point over the past 12 months. In addition, very low food security is on the rise. In fact, 24% of all MA households experienced very low food security in 2024.”

Fact of the Week: 1 in 7 Americans Rely on Food Pantries – https://www.chn.org/voices/fact-week-1-7-americans-rely-food-pantries/

Some food banks see up to 1,800% surge in demand since SNAP benefits were halted – https://abcnews.go.com/Health/food-banks-1800-surge-demand-snap-benefits-halted/story?id=127410295

More than half of Americans are one paycheck away from disaster.

But but but … tax cuts for the rich … destroy neighborhoods for profit … get rid of every kind of safety protection … get rid of protections against corruption … pardon profiteers … outlaw protest … must stop now!

KiA, Whether it is your disgusting tropes invoking the homeless or the hungry in America or your constant invocations of the left, you make me feel embarrassed to be a Republican these days. I don’t know if your actions here are a result of you being uninformed, misinformed, or a intentionally malignant rationale. Please knock it off.

David,

Yes KIAs social tropes are indeed disgusting. I can never quite work out whether KIA is uninformed or just likes trolling to annoy people. I have settled on the most likely answer being a combination of both. I used to respond to his comments , now I mostly ignore him.

I doubt KIA will knock it off. He’s been doing it for years and has been asked to knock it off many times. No sign of that happening sadly. I suspect he’s a paid troll working for some sort of lobby group. Based on his claims, his polite demeaner and other things.

Good on you for taking a position on these issues that might annoy some of your fellow Republicans. You come across as a political moderate. I lean more towards liberal end of the spectrum but I often find myself having to criticise fellow liberals when they talk crazy stuff or make incorrect claims about the other side of politics. Sadly it doesn’t make me very popular at times. But its important to avoid group think.

Nigelj,

With the passing months, paid troll theory seems to be a winning bet, lol. I probably should be a bit more measured or just disciplined to ignore his clockwork-like appearances, but…

Hunger in particular ever being evoked to troll just pisses me off. Any person who spends even a one-time, part of a day effort helping on a food drive or helping at a food bank can see the truth. It is not an endless progression of the entitled or lazy. What I’ve seen in my trivial fleeting efforts are enough to rip your guts out looking at eyes of pain, or shame, or little kids not understanding, or how many these days are working poor as Susan Anderson forcefully shows above. In the wealthiest most powerful nation ever! Sorry Nigelj, I know from reading your comments here at RC you understand. Sorry for rant. This paragraph is for KiA.

On the moderate R read, yeah. I guess, lol. I sometimes wonder if I hadn’t spent my formative years in a largely conservative part of the country raised by a family of R’s and instead raised in largely D areas if I’d ended up calling myself a conservative D? These days, it’s easy. I only vote for people who understand what scientists contribute, the environmental issues I’ve cared about since my teenage years and how it keeps deepening with each year, AGW, etc. Oh, and actually believe keeping liberal democracy around is essential. Not big on fascist crap obviously. Lastly, no flavor of democracy has the market cornered when it comes to good ideas or best practices.

I was a bit surprised to read how you described yourself. I had you down as maybe a bit more moderate type fellow. I do admire people of any political stripe who don’t shy away from giving voice to members of their own with whom they part views.

Maybe that’s why I am rather appreciative of the regulars here. Most I think are liberals, yet are accepting (or tolerant? lol ) of wayward conservative souls like me!

David,

Regarding the climate denialist trolls like KIA. I think its fine if you want to respond to KIAs comments. I have just got bored with responding to KIA and I don’t want to repeat myself too much. Happy to read others responses.

Zebra says ignore the denialist trolls, and creates quite a good case for doing this, but I just cant quite agree with him. I think it is often a good idea to respond to them and at least to spell out the climate facts for the benefit of the wider audience. And sometimes its worth debunking their political views.

Regarding foodbanks. I have never been involved with foodbanks but it seems a reasonable assumption that people would be there for a wide variety of reasons such as job losses. wage cuts, emergency expenses, inflation, and perhaps a few are lazy and users or drug addicts Its one of those things where its dangerous to generalise or be too judgemental. And when guys like KIA generalise and seem to think its all the victims fault I do get irate.

Regarding politics. My understanding is we all lean either liberal or conservative and we are born that way, but that we are able to change our positions. Its not an absolutely fixed thing. Theres some research into this but I dont have time to dig it up.

However Im fairly moderate in my political views. Just because I lean liberal doesnt mean Im at the extreme end of that spectrum.

Liberals are generally quite science focused and quite intolerant of anyone that attacks science. I certainly am.

Gavin, thank you for the interesting post serving as an entry into a critically complex subject. Kinda nice for a change reading a post here and not having to flail about in my usual manner trying to understand the subject being presented ;-)

On the subject of climate change economics, those with financial and/or political motivations to maintain the fossil fuel powering of economies have been handed a new club (courtesy of the journal Nature) to pound the ground as they are already writing and talking to the public to shout “fraud”:

“RETRACTED ARTICLE: The economic commitment of climate change”

“This article was retracted on 03 December 2025”

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-024-07219-0

AP News story on this:

“Researchers slightly lower study’s estimate of drop in global income due to climate change”

https://apnews.com/article/climate-change-economic-impact-global-emissions-nature-3b99e4c317214554d28decf253bad3bb

I don’t doubt the need for real, sincere, serious discussion that must occur. I only hope that the individuals involved will address this not only from the academic perspective, and talk to respected outlets like the AP, but also not shy away from confronting those whose aims are pointedly corrosively singular.

I know my perspective on the need for communication/confrontation with the voices who spout half-truths or extort matters like this to their audience about climate change science is not popular here, but, so be it.

“I know my perspective on the need for communication/confrontation with the voices who spout half-truths or extort matters like this to their audience about climate change science is not popular here, but, so be it.”

If you are paying attention to people who try to derail you here, you give them power by giving up. Please don’t. Unfortunately, the free for all in these comments, including those who are right but won’t let go as the back and forth lengthens ad nauseam, discourages what could otherwise be a useful conversation.

Just saying “Hi,” Susan. It’s been months since a visit. And it makes my day to see your continual energy here.

Yes, I remember a link you provided to see more of you. I may yet try.

Just so much work here preparing for the accelerating exponential curves colliding soon. I’m kind of becoming a prepper of sorts (not the crazy sort so much but more of a balancing flywheel for my wife’s more worried side) on an acreage of some size with all my family and grandchildren here with me. We are moving towards growing, preparing, learning about year long storage methods, local food diets vs food that must be shipped in, etc. Shifting more towards physical labor over power tools… I’m 70 now but healthy and able to use two 8 pound splitting mauls, one in each hand, to split logs in storage.

The hardest part is attracting good talent, setting up a talented board of directors, and making a market for those who may need to leave and take fair value out without seriously injuring the organization, too. But I’ve found and attracted some good talented people. So moving along in the right direction. Ownership and personal investment in outcomes is important for all.

Hard, but invigorating and enjoyable for this retired practical physicist engineer. And being surrounded by equally good people is …. Indescribably wonderful. I’ve been lucky.

Susan, my wife is my first and only for more that 45 years. She’s way smarter than me in complementary ways — more long term views, white I try to detail the next few weeks at most in completing the short term. She sees what I cannot see well. I complete shorter term objectives that move us more or less in those directions she sees ahead. It has worked well. And we have succeeded well as a team.

I probably won’t write again for a white. But you have my profound respect and I only wish I may have has a chance to benefit from knowing you better as a person and friends.

My love and hope for the best for you. (These debates here are mostly a waste of breath and emotional energy.)

Jon, wait! You have to explain the “two 8-lb mauls thing”!

My first visualization was someone with very narrow shoulder width splitting a 36″ round into three pieces with one 16lb blow. Not likely I think.

So are you both ambidextrous and very strong, and you attack the wood left-right left-right, like beating a drum?

I know you aren’t using one maul as a wedge and hitting it with the other, because that would be bad physics, right? ;-)

I really am curious as to what you meant there. I stopped using an 8-pounder a while ago… my spine is pretty dinged up, and 3 1/2 works quite well for me. I’ve had an (unfortunate) abundance of dead ashes and oaks, that have few knots.

Anyway, good luck with your project. And this year I finally got an electric chainsaw, which I highly recommend if you are doing more cutting.

I typically have fairly large trees, about 2.5 to 3 feet in diameter to work with. A deck of logs will be about 15 to 20 trees each after cutting/trimming about 50 feet long. and not much taper. That’s almost fills my 42 foot by 15 foot storage, I think. (I’m looking at this last summer and my storage structure I built myself here.) I use a Stihl 461, myself, I have built myself by hand a powered splitter because my son refuses the physical labor that I much prefer. and my grandchildren are 14 and under and he works with them. I work alone and enjoy the time very much.

The two handed maul approach is used just as you say. I put everything I have into the first strike. Others I try to teach are timid about it and find they cannot split log pieces (about the length of my chainsaw bar length thick). I believe fully in myself and entirely commit to the strike and usually succeed. But pieces vary and some require another go. Some are knotted/twisted enough that I leave the first maul embedded and then use the second maul to finish.

No, that’s not bad physics. Years of training myself and long experience says otherwise.

I absolutely love this work. It is a pleasure. Not a burden. I won’t use the powered splitter I built because it’s just no fun and it doesn’t invest in my body. When you get good at something it becomes something you appreciate and love. And this is one of those.

I have smaller axes because my wife won’t use the 8 pound maul. But she can’t really produce much, either. And doesn’t contribute much. It is just for special times when I’m not present and only then for already split pieces she wants as kindling.

The 8 pounder is the workhorse size, I think.

Jon K

Jon, I keep splitting by hand for exactly the reasons you do. But just thinking about how much the sections you are talking about would weigh makes my back hurt as I sit here typing.

I’m getting the season’s first dusting of snow this morning, and the woodshed looks charming (and full!), so I will have some more coffee and read the latest not-very-pleasant news.

Anyway, carry on, and again, good luck with the project.

This thing where you cut down trees to burn as firewood. Wow a new energy technology to reduce pollution and cutdown on CO2 emissions I hadn’t heard of.

People can hold strong abstract beliefs about emissions while being psychologically insulated from the material reality of their own energy use. It’s normal. Happens the world over.

Neurodivergent,

This thing where you cut down trees to burn as firewood. Wow a new energy technology to reduce pollution and cutdown on CO2 emissions I hadn’t heard of.

People can hold strong abstract beliefs about emissions while being psychologically insulated from the material reality of their own energy use. It’s normal. Happens the world over.

Superficially you make a good point. But people are all emitters of CO2 every second that they’re alive too just by breathing. It’s something that they can’t help. I suppose that they can take their own lives but … that doesn’t make their act of breathing wrong.

There’s a big difference between what a person has to do individually or as the provider of his/her family (and who cannot use a clean alternative because it’s either unaffordable or unavailable) to not suffer and what a giant ff corporation can do to stop emitting CO2 by changing to a clean alternative, both in the ability to change and quantity of CO2 emitted. They have the means but they choose to fight it to protect their profits.

From what I can see those in the discussion are merely joking about how they split the wood they have to use, not delighting in hypocrisy

@RonR,

Ron, of course you are exactly correct. And I would point out that, as with many issues, the good/bad question is best answered by “it depends”, not broad generalizations.

In my case, I only cut down dead trees on my property… as I said, unfortunately all my Ashes and Oaks have been dying over the time I have lived here. In fact, more have fallen over than I have cut. I was just talking to a guy who locally harvests wood for sale on a small scale, and he said he hasn’t seen a live Ash in 15 years.

So, what is supposed to happen to those trees, or the healthy ones that get cut down because the home insurance companies see them as a risk, or to protect electric lines, or those cleared for developments, and so on?

The point is, the economics and environmental impacts vary enormously from locale to locale; sometimes it’s actually a net environmental benefit to use wood as an alternative energy source… and often it definitely isn’t. You have to work through the math in detail.

Zebra, I had a pine that had a big fat worm/slug like thing in it from the Pine Bark Beetle. Gross to look at. It’s because warmer temperatures in winter haven’t killed the beetle that cold temperatures historically have. It died and I had to pull it down. My guess is that is what killed the pine trees that you can see behind me here:

https://midmiocene.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/100_0558.jpg

You know this but I’ll say it anyway. Ash trees are similarly affected. The Emerald Ash Borer overwinter under bark. Sustained temperatures around -22 degrees F used to cause high mortality. With warmer winters they are surviving to spread and kill.. Oaks are killed by the Oak Processionary Moth. Same process. Their eggs survive better in mild winters. Same story with Oak Bark Beetles and Borers. Increased survival over winter.

There are various ways to treat them but they are complicated. It includes removing infested trees to prevent the spreading of the beetle, and planting drought and beetle resistant varieties. in their place. I cut down trees only as a last resort. It’s very sad.

Jon Kirwan, why thank you kindly.

I talk a good game, but that’s the easy part. Backatcha!

Jon Kirwan: forgot. Hangout for weather and climate updates, along with a lot of other foofaraw (Disqus comments are a free for all). Masters and Henson are the best.

https://yaleclimateconnections.org/topic/eye-on-the-storm/

Thanks for the link, but I’m way past their target audience. I skimmed it. But nothing new to me.

You don’t just talk a good game. I can see through that enough to see instead someone I would love very much as family. I only feel a profound loss from not having met you and being able to share a piece of each other’s minds. I would be so much the better for it, I’m sure.

I try to surround myself with people I can trust to have my back when that isn’t easy for them and when they may disagree but are still there anyway. And I want to be there for them when that also isn’t easy for me and I may disagree, but where my only response to them is “What do you need? How may I help you?” That is what being a true friend means. Not fair weather, when it is easy. But being there when it is hard and picking up the pieces if things aren’t so smooth. That’s when you are tested. That’s when you know your true friends from those who aren’t.

I think I’d want to be such a person for you and I think I could trust you’d be that person in return. And there’s no price to place on that.

I feel that loss. And I love the person I do see in your writing. Get that much right.

I’m trying Susan, I’m trying lol ;-)

BTW: Superb dose of facts on hunger in America by you above thread. Your friend Jon is spot-on. You are a marvelous voice in the RC commenters’ chorus with your contributions (and patience!). Agree or not, I always (well almost always) feel like it is time well-spent!

“Thus, a home built in 1976 that Zillow values at over $400,000 is now actually not worth anything”.

I’ll have two, thanks.