The Paris Agreement temperature limits are a little ambiguous and knowing where we are is tricky.

The desire to keep global temperature rises since the pre-industrial, ideally below 1.5ºC and definitely below 2.0ºC, is a little bit complicated by the lack of definition in what constitutes the pre-industrial, uncertainties in what the temperature was in the pre-industrial, and an ambiguity in what counts as exceeding these limits.

These are old questions that were tackled in prior IPCC reports (SR15 and AR6), but there are new elements that have come in to the equation since then and, of course, the real world has got closer to exceeding 1.5ºC and so there is additional salience. There is a big collective effort going on to provide some clarity on these broader questions (Update: preprint available here), but I thought it would be interesting to review some of the more technical questions here.

First off, when is the ‘pre-industrial’? It’s not really definable from history without going back to periods when we didn’t have any (or much) instrumental data, and as we’ve discussed, anthropogenic impacts on climate might date back to the dawn of agriculture. So, for practical reasons, people have settled on the 19th Century as ‘close enough’. But even there, we have issues. The early 19th C was abnormally cold because of a series of big volcanoes (incl. Tambora in 1815), so that shouldn’t be included if you want to highlight anthropogenic changes. In any case, the instrumental data sets for temperature are mostly only good for the global mean (with some relevant uncertainties) from 1850 onward (though there are some good efforts to push this back further e.g. Lundstad et al. (2025)). And since you need a few decades to smooth out the internal variability, people have been using various multi-decadal averages around then. While there are still a few holdouts, most folks have followed the IPCC lead and are now using 1850-1900 as the baseline for ‘pre-industrial’ in practice.

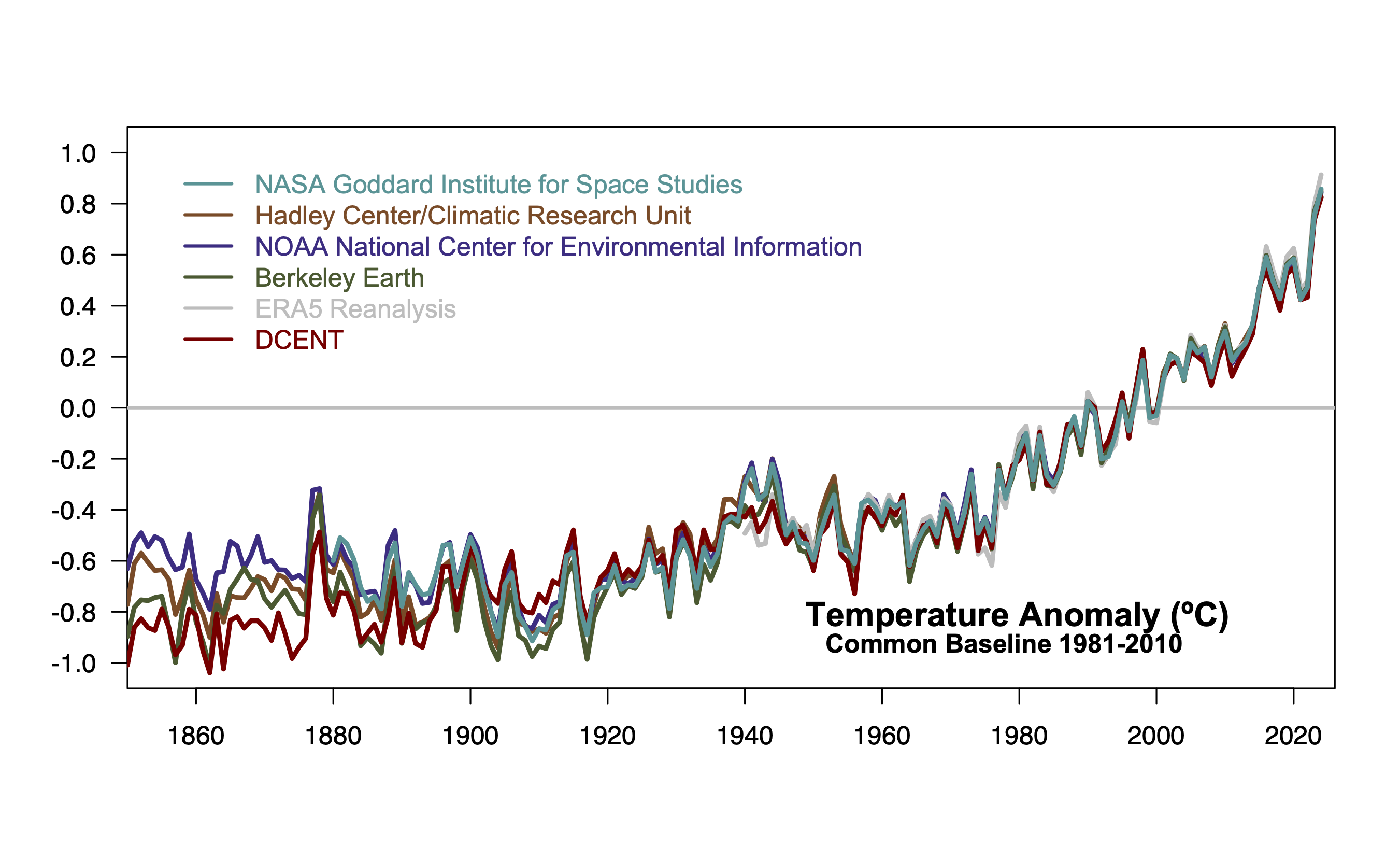

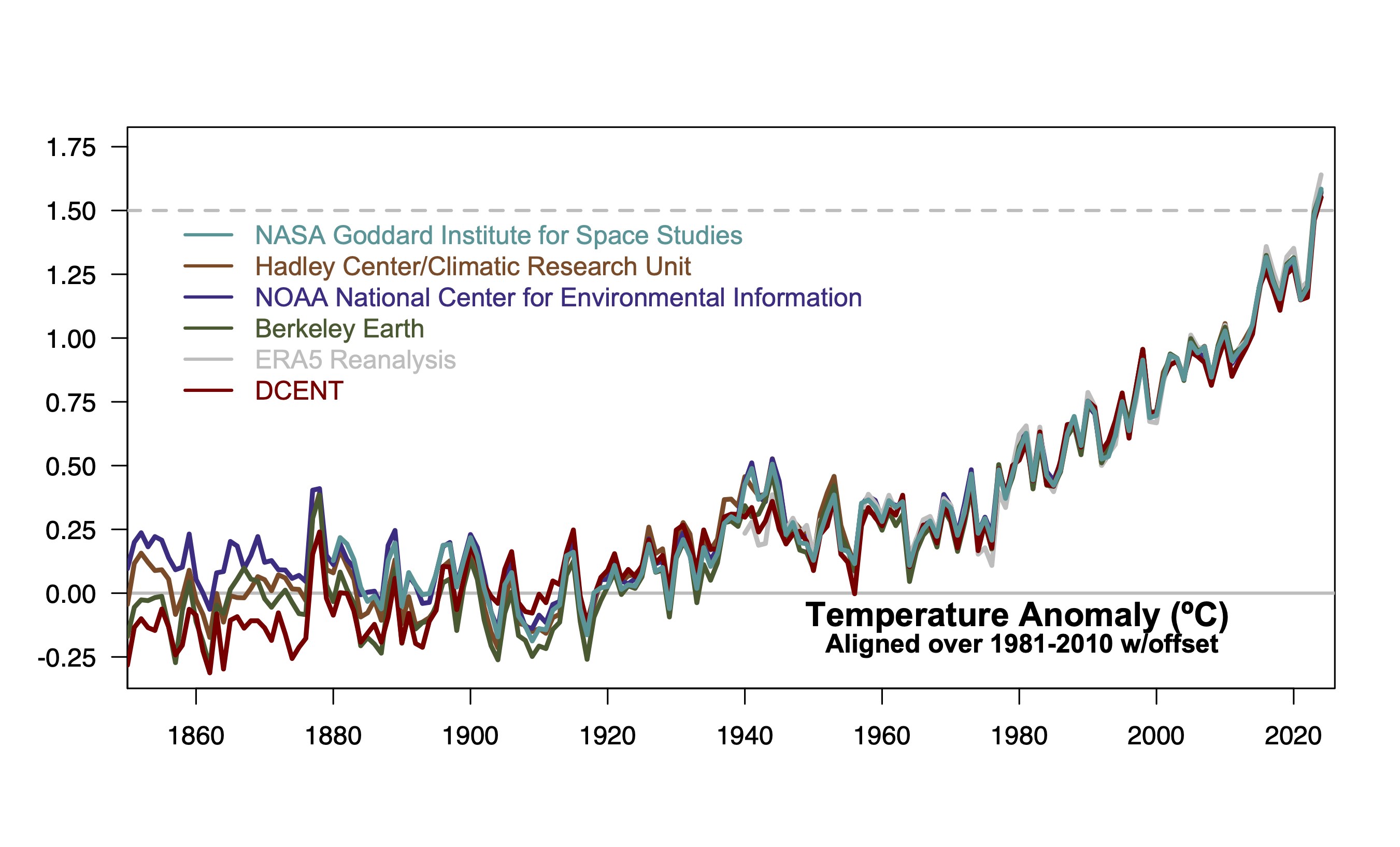

There are now at least four data sets that are regularly maintained and that go back to at least 1850: HadCRUT (currently v5.1), NOAA (v6), Berkeley Earth and, a relatively new effort, DCENT. They use different (though overlapping) raw data, different methods, and different interpolations, and thus (unsurprisingly) give different magnitudes of change since 1850-1900. With respect to their own baselines, 2024 was 1.45-1.65ºC above 1850-1900. If they are aligned in the modern period (when the differences between the methods/data are minimal), there is clearly a variation in both inferred interannual variability and mean change in the ‘pre-industrial’ period (see fig. 1). How should this be interpreted? It’s not the full structural uncertainty (since we are not really sampling all of the issues – particularly in the SST products), but it is perhaps a lower bound on that uncertainty. Ensembles that sample the methodological uncertainty are also useful, of course.

Other datasets such as GISTEMP or JMA, or the more modern reanalyses (ERA5, JRA-3Q etc.) that don’t extend that far back, can still be useful because they add to our understanding of the structural uncertainty in the periods where they overlap. The WMO uses a mix of these records (in 2024 it used an average of HadCRUT, NOAA, Berkeley, GISTEMP, JMA-3Q, and ERA5) when they are available to create a composite record. But how do we get the change since the pre-industrial?

As we discussed earlier this year, one way would be to baseline each long record to their own 1850-1900 data, and then add in the shorter records by tying them to one master record (but which one?) or an average of the longer ones. However, if you plot this out it gives the impression that all the uncertainty is in the modern period. Using a modern period to cross calibrate the different records (as in figure 1) but then imposing a constant offset to translate from the modern to the pre-industrial allows the uncertainty to be clearly associated with the past (not the present) (as in figure 2). But how should the offset be calculated? We could either assume that the average of the four long records should be zero over the pre-industrial period or that the WMO average should be zero (or even something else entirely).

How much does this matter?

First, the baseline issue. With respect to 1850-1900, using an average of the 4 records mentioned above, 1880-1900 is 0.01ºC cooler and 1880-1920 (which Jim Hansen uses) is ~0.02ºC cooler. These are small numbers on average, but the spread across the 4 records is large (±0.08ºC) indicating that this is not very robust and could change in future. Second, the difference between setting the WMO average, or the average of the 4 long records, or the average of the records that were used in AR6 to zero, can make a ~0.04ºC difference.

For individual months, there is a secondary issue – should you adjust the climatological baseline on an annual basis or on a monthly basis? Different months have warmed differently since the 19th Century (Jan/Feb/Mar have warmed by about 0.17ºC more than Jul/Aug/Sep). That is, do you consider the anomaly for Oct to relative to the climatological Oct (which seems sensible) or to the climatological annual mean? (which is slightly easier). For Berkeley Earth, October 2025 was at 1.52º above pre-industrial Octobers, or 1.57ºC above if baselined annually. Winter months are affected oppositely. Depending on the month it is an effect of ±0.08ºC. Note this is only an issue for the monthly anomalies w.r.t. to a different baseline than the native baseline (usually modern) for any particular product.

Finally, given that all of these approaches rely on moving targets (which records are being maintained, raw data being added through data rescue efforts, updates to method versions etc.), one has the choice of either updating these calculations every year (which means you need to explain why things might change from previous years), or sticking to a canonical calculation (such as the one in AR6) for consistency. The best estimate of the annual offset from 1981-2010 to the 1850-1900 period was estimated as 0.69ºC in AR6, but following an analogous recipe now would give 0.73ºC (mainly because DCENT has a colder 19th C than the older products, and updates to HadCRUT and Berkeley Earth have shifted things slightly).

The offset to tie the shorter records to the longer ones also varies over time if you keep the same method. For GISTEMP, I’ve been calibrating to the other records over the 1880-1900 period. Last year, that gave an offset of -0.028ºC to go from 1880-1900 to 1850-1900, but this year (with the addition of DCENT and minor updates to the raw data), it gives an offset of -0.01ºC. Copernicus uses a fixed 0.88ºC offset (from AR6) to go from a 1991-2020 baseline in ERA5 to 1850-1900, but following an analogous recipe and adding in DCENT, you’d end up with 0.92ºC.

Last year was the first in which we “likely” exceeded 1.5ºC in the annual average (the WMO average was 1.55ºC), and the assessed uncertainty in this (arising from all the mentioned issues) is about ±0.13ºC (90% CI). With updates to the records, the WMO average would now be 1.54ºC. But if you added an offset to the 1981-2010 baselined data so that the average of the four long records was zero, 2024 would be at 1.58ºC. Adding an offset so that the WMO average was zero over the baseline takes you back to 1.54ºC.

On a monthly basis we have been exceeding 1.5ºC in the individual records (briefly) since the El Niño event of 2016 (maybe 2017 and 2019, and then again in 2020). Since 2023, we have exceeded it on a monthly basis more often and that has been sustained in 2024 and 2025 (figure 3).

Knowing when we’ve exceeded the limit with respect to a longer term average is trickier again except in hindsight. If we want to know if we’ve gone past the mid-point of the first twenty year period above the threshold, that involves some forecasting for the next ten years – which adds to the uncertainties. We have many forecasts – from CMIP, initialized projections, statistical fits, even machine learning – but there are many uncertainties (in the projected forcings, the structure of the fit, the appropriateness of training data). So this too will be something that is subject to (annual?) revision, and the precise answer might not be available for a while. Whether it matters if it turns out (in a decade or so) to have been 2028 or 2030 or another year is not obvious to me.

Summary

There are some irreducible uncertainties in defining where we are with respect to the pre-industrial at any one moment (day, month, year, decade), and so one shouldn’t expect to know this precisely, and one can expect a bit of ‘jitter’ in the assessments. Right now, while we are hovering around the 1.5ºC level, differences in method can move the value slightly above or below the threshold, but it should be understood that these jitters are not scientifically meaningful. The long term trends are.

References

- E. Lundstad, Y. Brugnara, D. Pappert, J. Kopp, E. Samakinwa, A. Hürzeler, A. Andersson, B. Chimani, R. Cornes, G. Demarée, J. Filipiak, L. Gates, G.L. Ives, J.M. Jones, S. Jourdain, A. Kiss, S.E. Nicholson, R. Przybylak, P. Jones, D. Rousseau, B. Tinz, F.S. Rodrigo, S. Grab, F. Domínguez-Castro, V. Slonosky, J. Cooper, M. Brunet, and S. Brönnimann, "The global historical climate database HCLIM", Scientific Data, vol. 10, 2023. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01919-w

This is a non-problem. The +1.5 °C crossing is fully measurable — the apparent fuzziness exists only because the baseline, datasets, smoothing, and crossing definition were never formally specified. Once these parameters are fixed, the crossing year is unique, empirically determinable, and mathematically straightforward:

\text{Crossing year} = \min \{ t : GMST(t) > \text{baseline mean} + 1.5\,^\circ\text{C (according to defined parameters)} \}

Since SR15 and the Paris Agreement, it has been possible to define these parameters and compute a single crossing year.

Data the issue is a non problem in a technical sense, but to get everyone to agree on formally specifying those parameters might be quite a large problem!

This post is really, really good. Thanks to all who worked on it.

Thank you, Gavin! Very precise and good overview regarding this subject. I think especially fig. 2 makes it clear, that different leaders in the last COP giving the impression that there’s still plenty of time to avoid crossing the 1,5-degree limit globally, are simply denying the facts. They are spreading big illusions, and there’s absolutely no reasonable doubt about why they are doing this: they are simply trying to deny that global heating has become dangerous, they are buying time for fossil capital by greenwashing the facts, as they have been doing all along. The result of this tactic is exactly what we can see: *the whole COP-process runs contrary to it’s official goals, and it does that more effectively than the open deniers like Trump, Putin, Bin Salman etc. alone are able to*. The majority in COP is in a rather subtle way functioning as their trojan horse, whether intended or not. Nothing implies that the crossing of the 1,5-degree limit in the years 2016, 2017, 2020, 2023 and 2024-25 should be seen as accidental outliers in the high end, meaning that the world soon will return to mean temperatures a bit below 1,5 degrees C above “preindustrial” – whether defined so or so.

Clearly the Earth doesn’t care what its temperature was in 1860. I know, there are lingering effects of heat or cold periods; but if we are wandering into conditions where positive feedbacks have started to dominate the climate, how we got here will matter a whole lot less than current rates-of-change. Except for “How do we argue with people who want to destabilize the climate for their own profit and comfort, who will deny any facts that threaten their energy-habit?”

Here is a GIFT link to the NYTimes flooding article linked to the final word “are” above. It’s a good series.

New York Is Going to Flood. Here’s What the City Can Do to Survive. It may have to throw every solution available at a worsening situation.

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2025/10/15/nyregion/new-york-climate-flooding-solutions.html?unlocked_article_code=1.AVA.PX_R.f5cdOhOi0zH0&smid=url-share

[graphical visualizations are very fine. Friends have told me you have to push though some advertising material to get to these links: please ignore them. Scroll to the end for links to resources used in article, like this one -> https://www.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=1c37d271fba14163bbb520517153d6d5

A slightly different analysis working backwards from today’s values?

“Earth’s average surface temperature in 2024 was the warmest on record, according to an analysis led by NASA scientists. Global temperatures in 2024 were 2.30 degrees Fahrenheit (1.28 degrees Celsius) above the agency’s 20th-century baseline (1951-1980), which tops the record set in 2023..”

Baseline (1951-1980)..January 1996: New York Times:

“One of the scientists, Dr. James E. Hansen of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Institute for Space Studies in Manhattan, said he used the 30-year period 1950-1980, when the average global temperature was 59 degrees Fahrenheit, as a base to determine temperature variations. He said his readings showed that the average global temperature rose about as much since the base period as it did from the 1880’s to the base period – about half a degree in both cases. He stressed that these were estimates and that it would take millions of measurements to reach an accurate global average.”

Thus.. 2.3°F above 59°F = 61.3°F., 16.3°C.

Subtracting the Paris 1.5°C threshold is 14.8°C. That’s only 0.8°C above NOAA’s 20th century average of 14°C.

Ken Towes calculation is wrong because he has mixed up numbers using different baselines, including NASA’s 1951–1980 baseline, NOAA’s 1901–2000 average, and the Paris numbers based on the pre‑industrial baseline. Maybe some other things wrong as well. And I don’t believe it’s a mistake as such. Its more likely carefully crafted dishonest deliberate manipulation to get the numbers he wants.

Folks have repeatedly explained to this denialist crowd why temperature anomalies are preferable to absolute temperatures. They just refuse to honestly listen. It’s Towe’s usual reflexive contrarianism and disinformation. Folks familiar with his posts know that what he’s going to say on climate change or climate policy will be as honest and insightful as what Eric Dubay’s going to say on Earth’s shape.

Examples of what I meant:

Towe is just another persistent denier looking to disinform people:

Honestly. I’m not sure what he thinks the point is. Why would you even think that the NOAA 20th-century average should differ greatly from the NASA 2024 average minus 1.5C? Is the point that this cobbled-together sequence makes it appear that post-1950 warming isn’t very significant? Even if we take things as given, that’s 100 years for 0.7C, or 0.007C /yr, versus 75 years for 0.8C, which is 0.011/yr.–more than 50% more rapid. It hardly seems worth the convolutions, if that’s the idea.

In response to Atomsk and Kevin’s replies, I would like to point out that for a layman there is one serious advantage to absolute temperatures rather than anomalies, namely that they provide a single point of comparison.

This is especially valid if the size and significance of the anomalies are subject to amendment from continuing research, because any such amendment is weaponised by the denialists.

I know that in my own case I look regularly (and with considerable alarm) at NOAA’s CO2 numbers from Mauna Loa. I read many years ago that the world should aim to keep this under 350ppm, and while this stays as the consensus target I can see at a glance that the current number is too high and still going up!

If COP produced a similar consensus target for the annual average temperature required to avoid long term deleterious effects, this would be a number comprehensible by innumerate politicians/general public. They might or might not accept the number, but either way Climate Research would now not have any political implications unless it changed the target.

ozajh,

“If COP produced a similar consensus target for the annual average temperature required to avoid long term deleterious effects,”

The problem is that we don’t have any consensus on quantifying “deleterious effects” and how they are related to GMST. And getting one is hardly likely, given that folks (certainly here) only seem interested in quibbling about tiny variations in GMST itself.

I’ve offered this statement several times as an illustration, inviting anyone to disagree:

“I say that it is quite possible that we could reach 2.5C and the AMOC would slow significantly, but that it is equally possible that we could reach 2.7C and the AMOC would keep going with little effect on European temps.”

And I’ve predicted correctly that nobody will even attempt to offer any scientific contradiction. But similar uncertainties exist about many of the main negative consequences of increasing the energy in the climate system.

So I would suggest that more qualitative information, with more localized focus, would be a better choice than continuing to quibble about GMST, a not very important metric (however it is expressed), if the goal is to educate the public and make the trolling at least a bit more difficult.

RC, Gavin, et al.:

How do you assess Nerem et al., 2018, concerning satellite SLR data collected and assessed since 1993?

Because temperature data analyses continue to be subject to dispute (in no small measure because of the time lags in collecting, assessing, and modeling data, apart from questions on reliability of 19th century and early 20th century data, etc.), I put the question to one of the LLMs whether SLR data are “less contestable”. With the expected caveats, the LLM allowed that the data treated by Nerem, et al., indicate global SLR since 1993 and also account for the rate of acceleration of SLR across the two decades or quarter-century worth of data.

Apparently, with those data in hand, proper attributions accounting for documented SLR can (and must) be made (that is, no one is arguing that water is seeping voluminously into our oceans from vast reservoirs in the Earth’s mantle or crust). Volumes of ice mass loss (Greenland, Antarctica, mountain glaciers worldwide) may still be disputed, but the losses themselves are known, as is thermal expansion within our oceans.

If in fact the LLM can be trusted almost as well as the available data, why do we not use SLR data as the “bedrock” of arguments concerning the increasing likelihood that Technogenic Climate Change has already emerged and threatens to erupt in cascading self-amplifying feedback loops sooner rather than later?

My biggest fear remains that, by whatever date we can claim to have incontestable temperature data of climate tipping points being reached and/or exceeded, any and all subsequent mitigation efforts will be of far less utility and efficacy, should they possess any such values at all.

The UNEP Emissions Gap Report 2025 delivers a blunt assessment: despite a decade of the Paris Agreement, global climate action remains grossly insufficient. Emissions are still rising, updated national climate pledges barely budge projected warming, and world policies are steering the planet toward nearly 3°C of warming – far above agreed goals. Incremental progress on renewables and pledges cannot mask the core reality: collective inaction persists, and without immediate, deep, and credible mitigation commitments, the 1.5°C target will be missed and climate risks will escalate sharply.

The 1,5 degree “target” has already been missed. As every thinking person knew already when this new red herring was presented. Remember? James Hansen said it in late november 2015: “The Paris agreement is pure, unadultered bullshit”. By now it’s evident that he was coreect. You could easily see that from the very beginning: this was just the next trick in the greenwashing pantomime, the symbolic “policy”making theatre, which has the main aim of almost all politics in the mediotic age: the “leaders” want to be *seen* ***as if*** they were doing something. They are making simulacra. And behind this depressingly monotonous scenery oiligarchic business as extrremely usual just goes on and on and on until the bitter end.

Already the word “target” lets the cat out of the bag, and it was of course not chosen by accident. The better expression would have been “limit”, if you really wanted to do what they just wanted to simulate they wanted to do. The people making all these smoke and mirrors up aren’t at all concerned about anything but again and again setting new imaginary “target”s – *which they know will be missed* – which again gives them the excellent opportunity to set up new “target”s – which they know will be missed – and so on and so forth, until kingdom come.

Imagine for a moment if our dear warmongering oligarchs were using this “climate” policy method in defence, instead of what they always do… Fx.: if any politician like the ones we now have almost everywhere: Netanyahu, Biden, Trump, Putin, Xi etc. etc. this newyears moring would say in his speech to his nation: “My goal is to use 1,5 trillion dollars more on armament in 2040. I deeply feel the urge to strengthen our defences. I begin this enormous effort, the likes of which have never been seen before in the history of our great nation, by proudly reducing the amount of money used on defence by one billion dollars pro year until 2035. Me and my fellow leaders urgently need those funds just to keep thinking about how great this nation really is. If you personally want to use more on defence, nothing is better than that, just send me personally or my and your government the money.”

Of course anyone sane who heard this, would still be laughing in 2040.

But nonetheless, defence experts would then endlessly deliberate about if the funds for diasarmament this or that year really had been reduced enough to guarantee that “we” would hit the “target” of one trillion more spent on armament in 2040.

Why is this so obviously absurd and laughable, but not the “climate” policy, which uses exactly this method?

Just think about it.

Reminds me of the very corporate friendly New Zealand government lead by Chris Luxon who says he’s “firmly committed to net zero by 2050”. Only problem is he has no convincing climate policies and has cancelled almost every single policy the previous government had for cutting emissions. I don’t know if the man is lying or really believes his own BS. Either way is all Orwellian doublespeak.

No, the 1.5 °C target has not “already been missed.”

While the Paris agreement is silent on methodology, the scientific convention, developed primarily by the IPCC, assesses 1.5 °C above pre-industrial using ~20-year running means, not a single year. Short-term excursions (single years or a few years above 1.5 °C) are not considered a formal breach of the Paris goal.

A multi-decadal mean is intended to filter out internal variability, and reflects the non-linear, probabilistic nature of climate risk.

Global Mean Surface Temperature is not a policy input chosen directly by governments, like your defense spending analogy suggests. It’s an emergent system outcome, resulting from cumulative emissions, inertia, feedbacks, and internal variability.

The IPCC SR15 explicitly uses 30-year averages, not ~20-year.

The key principle — short-term fluctuations don’t count — is correct. But the formal definition is precise:

Global warming: The estimated increase in GMST averaged over a 30-year period, or the 30-year period centred on a particular year or decade, expressed relative to pre-industrial levels unless otherwise specified.

For 30-year periods that span past and future years, the current multi-decadal warming trend is assumed to continue. {1.2.1}

https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/spm/spm-core-concepts/

In AR6, when discussing the time of crossing a temperature level (e.g., 1.5 °C), they use the 20-year running mean as a convention for determining when a sustained exceedance occurs. More specifically, it represents the first 20-year period whose averaged temperature exceeds the threshold.

In your link to SR15 they use the 30-year averaging period for determining warming.

Both approaches aim to filter out short-term variability and focus on long-term trends.

The difference is in the context. SR15’s 30-year averaging emphasizes historical and present warming estimates, whereas AR6’s 20-year criterion is used to define the crossing time of future projections.

Reply to Crusty Caballero

4 Jan 2026 at 9:47 AM

Crusty’s claim that AR6’s 20-year running mean “explains” SR15’s methodology is simply wrong.

As I described above, SR15 explicitly defines global warming as the GMST averaged over a 30-year period, centered on the year or decade of interest, to quantify when thresholds like +1.5 °C are crossed. This is the framework used to interpret the Paris Agreement goals.

AR6’s 20-year mean, by contrast, applies to future projection scenarios and was not even finalized when SR15 was produced. By collapsing these two distinct methods, Crusty commits a category error: historical/observed warming estimates are not interchangeable with scenario-based projections.

The 30-year SR15 convention is the definitive basis for calculating threshold crossings — nothing else, unless and until the IPCC revises its definitions by scientific consensus.

No, I never claimed that “AR6’s 20-year running mean “explains” SR15’s methodology.”

Please read my post again, and respond to what I wrote rather than what you think I wrote.

I’m simply saying that the IPCC uses the 20-year running mean as a criterion to define the crossing time of future projections.

Quoting from AR6 – Chapter 4, Future Global Climate: Scenario-based Projections and Near-term Information, page 555:

Crusty Caballero says

5 Jan 2026 at 6:39 AM

My point was — and remains — that this is irrelevant to SR15’s Paris-mandated 30-year GMST definition. Repeating AR6 scenario conventions does not address that point.

FYI, Crusty Caballero:

‘Data’ is a sockpuppet account of someone who’s trolled this forum for years under various sockpuppet accounts. Your point on the 20-year running mean has been explained to them multiple times, with supporting evidence. They just never honestly admit when evidence shows they’re wrong; it’s one of the tropes of their accounts. It’s one of the reasons many people on here have taken to ignoring their spam.

https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2025/12/unforced-variations-dec-2025/#comment-843341

What does evidence look like?

AR6 SSP framed scenarios dependent on a range of emissions levels, and the 20-year running mean, have nothing to do with the Paris Agreement nor a SR15 1.5C “crossing point”. Or this article published by Gavin.

In support of Crusty Caballero’s point about the 20-year mean being used for the Paris Agreement targets, and 1.5°C not being reached yet for those targets:

Re: “AR6 SSP framed scenarios dependent on a range of emissions levels, and the 20-year running mean, have nothing to do with the Paris Agreement nor a SR15 1.5C “crossing point”. Or this article published by Gavin.“

Incorrect, sockpuppet account. The Paris Agreement limits are based on the value at the middle of the 20-year mean. That necessitates making a projection for the future (i.e. a projected scenario), as covered in Dr. Gavin Schmidt’s article that you neither read nor understood:

I doubt you’ll honestly admit you were wrong on this, anymore than you admitted it the numerous other times you’ve been shown to be wrong across your sockpuppet accounts.

https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2026/01/unforced-variations-jan-2026/#comment-843479

Atomsk’s Sanakan

Yes, he’s clearly trolling, refusing to address the subject of my sub-thread.

So far he’s tried a straw man, a red herring, and a gish gallop. What will he try next!

What counts as evidence here is the relevant IPCC assessment commissioned under the Paris Agreement, not later summaries, dashboards, images or individual papers.

From IPCC SR15, Summary for Policymakers, Box SPM.1 (Core Concepts):

Global warming:

“The estimated increase in GMST averaged over a 30-year period, or the 30-year period centred on a particular year or decade, expressed relative to pre-industrial levels unless otherwise specified. For 30-year periods that span past and future years, the current multi-decadal warming trend is assumed to continue.” {1.2.1}

https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/spm/spm-core-concepts/

SR15 explicitly defines global warming for Paris target assessment using a 30-year GMST average (SPM Box 1.2.1). That definition was adopted precisely to standardise how threshold crossings like 1.5 °C are assessed.

Later uses of 20-year means in AR6 scenario projections, WMO summaries, or individual studies and snapshots do not retroactively redefine SR15. They serve different purposes and operate in different contexts beyond the IPCC.

Citing secondary sources or post-hoc conventions does not alter the IPCC SR15 methodological basis for defining the Paris 1.5 °C ‘crossing point.’

Crusty Caballero says

6 Jan 2026 at 1:12 PM

Everyone chooses what they will believe. It’s not my role to hold their hand, say it’s OK or prove they’re wrong.

Re: “Yes, he’s clearly trolling“

Yup, as illustrated in his blatant self-contradiction about the Forster 2025 paper. That paper confirms your point about how the Paris Agreement thresholds are based on the long-term 20-year value. So they troll about it.

I really struggle with scientists who waste energy talking about how to split up things into neat divisions. How many continents are there? How many oceans? Or seas? Is Pluto a planet? These are all human constructs.

Here you are talking about an arbitrary increase from an arbitrary baseline in an arbitrary year. You waste all this brain power trying to compare now with some mythical perfect average planetary temperature in 1850 (or was it 1800? or 1780?). Typically (other than with climate science) the industrial revolution started in 1760, why not use that date? Or would it be more appropriate to base it on when humans first started large scale land clearing? Which of these dates had the perfect climate?

“Right now, while we are hovering around the 1.5ºC level” – Under which metric are we worse off than 1850?

And the single most important question to consider – which year in human history had the “best” temperature?

Happy New Year all

We want to see the trend, Keith. That means we have to compute a global baseline temperature for some period and then compute a global average temperature for each year after that. Then we draw a graph of all the yearly points and we include the baseline. We connect the dots and we can see the trend, up and to the right.

You’re correct that we can use any baseline we want, but we need temperature data to compute the baseline, and before 1850 there wasn’t enough. Also, the period from 1850 to 1900 was when the *US, and a lot of the world, changed from burning wood for energy, which does not add to the greenhouse effect, to burning coal for energy, which does add to the greenhouse effect.. So it makes sense to use that period as the baseline.

in Re to Martin Smith, 31 Dec 2025 at 4:37 AM,

https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2025/12/1-5oc-and-all-that/#comment-843296

and Keith Woollard, 29 Dec 2025 at 10:21 PM,

https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2025/12/1-5oc-and-all-that/#comment-843296

Dear Martin,

I understand the idea to put the baseline as a trade-off between sufficient certainty with respect to data availability and quality on one hand and minimal fossil fuel consumption on the other hand.

I only somewhat doubt about your statement “burning wood .. does not add to the greenhouse effect”.

So far, it was my understanding that this assumption applies only if the carbon pool existing in form of biomass remains constant. I thought that if it shrinked due to accelerated oxidation to carbon dioxide by biomass burning (irrespective whether it is for energy or in forest fires), it would contribute to the rise of atmospheric CO2 concentration (and thus to the rise of its greenhouse effect) as well. Am I wrong?

Dear Keith,

I understand your objection that disputing the “right” baseline for a trend may look as hair splitting, especially when it is already quite clear that there is indeed a temperature increase (irrespective whether we put the baseline to any time span between, let say, 18OO and 1900) and that more relevant for practical purposes than estimation of the most suitable baseline might be estimation of the right slope. On the other hand, as a layman, I can imagine that both tasks may not be easily separable from each other and that it can be the reason why climate scientists still dispute both.

Thank you, Martin and Keith, for your contributions, and all the best for the next year!

Greetings from Prague

Tomáš

You’re right about deforestation, TK, which is what was happening back then and is still happening today, but my point is that living trees are in the carbon cycle, so if you cut down a tree and burn it, you are returning CO2 to the atmosphere that was recently removed. That’s quite different from burning coal, which returns CO2 to the atmosphere that was removed from the carbon cycle during the Carboniferous geologic period.

Keith Woollard: “ Under which metric are we worse off than 1850?”

Sure – nothing to see, all is for the best in this best of all possible worlds, prof. Pangloss.

Keith Woollard – “Which of these dates had the perfect climate”

How many angels can dance on the head of a pin? Your question is poorly formulated (perfect for whom – colonial powers in Europe? nomadic tribes in central Asia? bushmen in Africa?), has no objective metric to judge higher or lower “perfectness”, and even if they had – provides no valuable insight – you can’t step into the same river twice – much less into a completely different river – what may have been “perfect” for the preindustrial Earth of a few 100 million of people may not be perfect for the 8 billion plus in the modern technological world.

Therefore, science asks question it can quantitatively answer – in this thread – what was the baseline temperature before significant CO2 emissions and the climate was in approximate

long-term equilibrium. And unlike yours – this question provides a valuable insight – allows us to see how far baseline climate we are being today and how further we will be under different emission scenarios in the future.

P: I haven’t actually seen the “when was the climate ‘perfect’ ?” argument for about a decade now. But like any good zombie, it appears to reassemble and arise from time to time.

KW: Hint. Climate “perfection” in any sort of the abstract is a ridiculous concept. Especially in any global sense. On the other hand, “survivable”, “supports economically productive agriculture”, “livable w/o 1st world economies”, etc. are not ridiculous concepts at all.

Piotr and jgnfld,

Perhaps I shouldn’t have used the word “perfect”, but the implication of this post and COP21 is that pre-industrial was “better” than now. I would strongly dispute that.

and jgnfld… you honestly believe early 19th century climate was more survivable or livable than now?

Keith Woollard: “ Piotr and jgnfld, Perhaps I shouldn’t have used the word “perfect”, but the implication of this post and COP21 is that pre-industrial was “better” than now. ”

Let’s test it – see if it makes any difference: ;-)

====

“How many angels can dance on the head of a pin? Your question is poorly formulated (“better” for whom – colonial powers in Europe? nomadic tribes in central Asia? bushmen in Africa?), has no objective metric to judge higher or lower “betterness”, and even if they had – provides no valuable insight – you can’t step into the same river twice – much less into a completely different river – what may have been “” for the preindustrial Earth of a few 100 million of people may not be better for the 8 billion plus in the modern technological world.

Therefore, science asks question it can quantitatively answer – in this thread – what was the baseline temperature before significant CO2 emissions and the climate was in approximate long-term equilibrium. And unlike yours – this question provides a valuable insight – allows us to see how far baseline climate we are being today and how further we will be under different emission scenarios in the future.”

====

So which of these arguments no longer holds?

KW: Do YOU believe on the basis of present knowledge that we are heading toward one MORE survivable to an average human out in the open than the 19th century climate, or LESS? Or are you planning for your kids to try farming on the Canadian shield when its climate is “perfect”?

Upon what, exactly, do you base your “belief”? Be specific.

You overlook the effects of more extreme weather. Also, the effects of rising sea levels, and rising ocean acidity levels. All of these will have a damaging effect on humans. I’m very much an amateur as far as climate science is concerned, but even I can see the flaws in your argument.

Sam Carana and I have gone back to include the Iron and Bronze age emissions, and we have the planet at 2.29C

Why ignore emissions from two epochs whose names indicate industrial processes!

https://kevinhester.live/2024/12/18/the-influence-of-climatic-change-on-the-late-bronze-age-collapse-and-the-greek-dark-ages/

in Re to kevin Heter, 30 Dec 2025 at 2:48 PM,

https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2025/12/1-5oc-and-all-that/#comment-843270

Dear Kevin,

If you are identical with Kevin Hester whose website you are referring to, please consider correcting your nick accordingly. And, if this website is indeed yours, I have a question to you:

If you do understand how Mr. Carana at https://arctic-news.blogspot.com/ arrived at setting the pre-industrial temperature (and perhaps also atmospheric CO2 concentration??) baseline to the year 3480 BC, could you explain? To me, his website cited by you seems to be somewhat messy.

Best regards

Tomáš

2.29 C is way off. The planet was approximately 14 C for many millenia. Even in the depths of an ice age the mean global annual temperature was 9 C.

Kevin Hetter: Why ignore emissions from two epochs (the Iron and Bronze age). whose names indicate industrial processes!”

Where is evidence for their effect on the global climate? The only plausible mechanism – via increasing atm CO2, would require sustained and significant increase in atm. CO2 starting in Bronze or Iron age and continuing to XIX century. Can you show it, and attribute it to their technologies?

Of course he can’t, because he evidently thinks that scale is irrelevant.

Keith Woollard: And the single most important question to consider – which year in human history had the “best” temperature?

Oh, for the love of dog! Keith, the single most important question isn’t about the temperature on a scale from 0 to 100, it’s the rate of change in temperature over time! We’re threatened by a comparatively high rate of change! Do you honestly need to be spoon fed this? It’s high school level analytic geometry!

If you must: the year that had the best temperature is the one with the annual temperature nearest the average of the last 5000 years. That’s when all of written history was made, during which GMST varied less than one degree from the average for the entire holocene (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41597-020-0530-7.pdf). We’ve now exceeded that range, and the rate of change in GMST may be accelerating!

IOW: It’s the trend, you incorrigible fool! I, for one, would have a happier New Year if you got that through your head!

Oh, I am so sorry Mal (and Martin and Tomáš), I read the article as though ” ideally below 1.5ºC and definitely below 2.0ºC” were scalars, I didn’t realise there was a time component involved.

It’s weird, if the COP21 attendees and Gavin meant it to be a rate it’s odd that wasn’t given.

….. but you would know best

Trend, Keith, the trend. Not rate. “The trend is your friend,” is what they say down at the stock market. Not so much here. Here the trend shows the global average temperature is increasing and the increase since the beginning of the fossil fuel age is well within the range predicted by models of the physics of the greenhouse effect. But you’re right, the rate of increase is important to, especially if the rate is also increasing, which the graph can also show..

So choosing a baseline is important. It doesn’t have to be the exact correct year. You just have to pick one that makes sense, and then stick with it.

Martin Smith: Trend, Keith, the trend. Not rate.

“The first rule of tautology club is the first rule of tautology club.” (R. Munroe).

“The first rule of tautology club is the first rule of tautology club.” (R. Munroe).

BPL: I’m stealing that.

Mal,

But Mal, when you and almost everyone else here spends all their bandwidth going on and on about small (and meaningless) variations in GMST, you open yourselves to exactly this kind of trolling.

And when I suggest, as I have for a long time now, that this narrow focus is poor communication/education for the hypothetical unbiased reader, the response is “well yeah, but someone just did a video saying it’s 1.6C by 2035 not 1.5, so we need to clear that up!”.

If you want to “correct” something, how about this:

I say that it is quite possible that we could reach 2.5C and the AMOC would slow significantly, but that it is equally possible that we could reach 2.7C and the AMOC would keep going with little effect on European temps.

I’m predicting that neither the actual experts nor the wannabees will want to explain the science of why that isn’t a reasonable statement.

Zebra: “But Mal, when you and almost everyone else here spends all their bandwidth going on and on about small (and meaningless) variations in GMST, you open yourselves to exactly this kind of trolling. […]And when I suggest, as I have for a long time now, that this narrow focus is poor communication/education for the hypothetical unbiased reader, the response is “well yeah, but someone just did a video saying it’s 1.6C by 2035 not 1.5, so we need to clear ”.

Not really – the response to you was a) that EEI is not a substitute for GMST, b) that it is EEI that is more, not less, vulnerable to misrepresentation and trolling, c) that we have many orders of magnitude fewer measurements of EEI than we have of T, d) that T is more relevant to many? most? of climate change impacts, and finally e) that in the context of communication/education – T is intuitively understandable/relatable by everybody, while your EEI – not so much.

This has been pointed out to you many times – your response was to either skirt the argument, or ignore it completely, and then repeat your long-standing narrative as if it has never been challenged. lecturing us again how GMST are “meaningless”, and how using T instead of your EEI is a “poor communication/education”. In short: EEI good, GMST bad! EEI good, GMST bad! EEI good, GMST bad!

==== A more detailed case against the supposed EEI superiority in climate science and its communication =====

Unlike EEI, T is intuitively understood by anyone who have ever seen a thermometer; is a variable that is easy to measure with a high precision thus has been measured countless of times all over the world over last 1.5 century, Yet Zebra chastises climate scientists for using GMST instead EEI in their work, and particularly in their education/ communication to the lay people. He insists that instead of GMST we must use EEI – a variable that lay people do not now it is being measured, a variable for which we have many orders of magnitude FEWER measurement than for T, and these that we have are from the last years? decades?, with nothing for the most of the period of human CO2 emissions, and no data in the preindustrial/geological past – since unlike T – there no icecore, sediment or microfossil proxies for EEI.

Further, EEI, unlike T, has hardly any clear connection to the effects of AGW that science and/or the public cares most:

1. it is T (with abs. humidity), not EEI, that determines air density and relative humidity – thus the vertical transport of heat in the atmosphere – and the altitude/temperature from which energy is radiated toward the space (flux of this energy is proportional to the fourth power of T+273.15K, not to the fourth power of EEI).

2. it is T that determines air-sea exchanges of heat, including the uptake of most of EEI by the oceans.

3. it is T (with salinity), not EEI, that determines water density, and therefore the rate of formation of deep water – therefore the strength of the very same AMOC that zebra have just used to lecture us on the superiority of EEI.

4. it is T, not EEI, that directly influence the capacity of the ocean to take anthropogenic CO2

(solubility of Co2 in seawater is a strong function of T),

5. it is the strong positive feedback between T and water cycle that strongly amplifies warming by human GHGs (7% higher water vapour saturation per deg. of T => AGW by higher absolute conc. of WV and/or fewer/higher clouds)

6. it is T, not EEI, that is directly linked to many ecological influences of AGW: metabolic rate, heat stress, protein denaturation, bacterial decomposition rates, lower oxygen availability in water – are all functions of T, not of EEI.

===================

zebra: you open yourselves to exactly this kind of trolling.

Sigh. We all open ourselves to trolling whenever we post here, z. Hell, trolls can make their own openings. Thankfully, some of us refrain from trolling better than others.

Mal: +++++

Additional compliments to Crusty C for: “So far he’s tried a straw man, a red herring, and a gish gallop. What will he try next!”

—

Also, trying to identify exactly what kind of troll is not a useful activity. We can hope Gavin Schmidt will take a look and get rid of a few more ringers.

Everyone chooses what they will believe. It’s not my role to hold their hand, say it’s OK or prove they’re wrong.

Brandolini’s Law, states that the amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude bigger than that needed to produce it.

https://modelthinkers.com/mental-model/bullshit-asymmetry-principle

Hot air rises as do lightweights.

Data said: “It’s not my role to hold their hand, say it’s OK or prove they’re wrong.”

Then why do spend so much time on this website trying to prove people wrong?

Nigelj says

8 Jan 2026 at 1:16 PM

Then why do spend so much time on this website trying to prove people wrong?

Unfortunately, you are directing that question to the wrong person. Wrong target, yet again. Persisting in it doesn’t improve the argument nor your subjective opinion.

Now run along. Come back when you have something of real value to contribute.

D: Now run along. Come back when you have something of real value to contribute.

BPL: I’m sure you can be more condescending if you really try. Make an effort!

Data @ 8 Jan 2026 at 8:23 PM

Data: Everyone chooses what they will believe. It’s not my role to hold their hand, say it’s OK or prove they’re wrong.

Nigelj : Then why do you spend so much time on this website trying to prove people wrong?

Data: Unfortunately, you are directing that question to the wrong person. Wrong target, yet again. Persisting in it doesn’t improve the argument nor your subjective opinion.

Nigel: I think I have exactly the right target. You are the only person around here making the claim “Everyone chooses what they will believe. It’s not my role to hold their hand, say it’s OK or prove they’re wrong.. While spending a whole lot of time trying to prove people wrong.So answer the question and stop evading and deflecting.

Data: Now run along. Come back when you have something of real value to contribute.

Nigel: Patronising insult. The usual resort of people who cant prove their point. And very ironic given the huge volume of waffly rhetoric you post.

I have nothing the prove. Nothing to evade. My comments stand on their own. Everyone chooses what they will believe. It’s not my role to hold their hand, say it’s OK or prove they’re wrong.

D: It’s not my role to hold their hand, say it’s OK or prove they’re wrong.

BPL: This is the fourth time you’ve posted the exact same wording. Are we talking to a program?

Not clear what you were trying to say there, Mal.

The trolling happens.

You respond to it.

Only then does it go on and on.

I’ve often described this as a form of co-dependency. Are the trolls the addicts, or the people who go on and on and on responding, or are they both addicted to trolling?

(I know you like to get philosophical from time to time, so feel free to sort that out for us.)

zebra says

2 Jan 2026 at 6:41 AM

Mal,………….., you open yourselves to exactly this kind of trolling.

Keith Woolard is not a ‘troll’ nor is he ‘trolling’ this forum. The same goes for others, even Mr Know It All. Yes ‘trolling’ happens here but it is rarely if ever performed by what might be considered ‘climate science deniers’ on this forum. Rather the opposite is what regularly happens here.

Disagreement and Differing Opinions ≠ Trolling Performed by a Troll

zebra says

8 Jan 2026 at 6:20 AM

I’ve often described this as a form of co-dependency. Are the trolls the addicts, or the people who go on and on and on responding, or are they both addicted to trolling?

That is a much better question to explore in a quieter objective space. Not here.

Data says: “Keith Woolard is not a ‘troll’ nor is he ‘trolling’ this forum. The same goes for others, even Mr Know It All. Yes ‘trolling’ happens here but it is rarely if ever performed by what might be considered ‘climate science deniers’ on this forum. Rather the opposite is what regularly happens here. Disagreement and Differing Opinions ≠ Trolling Performed by a Troll”

Of course Woolard and KIA troll this forum. They both make inflammatory or offensive statements clearly to annoy people. That is the dictionary definition of trolling: making inflammatory or offensive statements to annoy the group.

Woolard does it by repeating his denier slogans. For example: “And the single most important question to consider – which year in human history had the “best” temperature?” This is annoying and obviously designed to be provocative. He does however make some constructive criticisms, so he isn’t constantly trolling.

KIA trolls virtually all the time for example with his climate posts about some snowstorm somewhere etcetera. In this forum that sort of rhetoric is inflammatory and annoying. He does it with frequent political posts virtually all of which are inflammatory and lies. KIA is a perfect example of a troll. You could put his photo in a dictionary definition on trolling.

Obviously not all deniers are trolls – some are polite and make reasoned and constructive criticisms. But many repeat stupid slogans and false accusations which are inflammatory so they are trolling in a climate forum setting. It’s obvious.

Nigelj,

The entire focus of this post is about the definition and measurement of pre-industrial global temperature so that we can keep within a predefined scalar of that.

Surely asking what value we should be aiming for is absolutely central to this quest? I am not asking to be inflammatory, and if you are genuinely offended I am sorry for you

It sounds to me like you are suggesting that the IPCC and CoP21 have made an edict that cannot be questioned.

No, Keith Woollard, it’s just trolling that commits the nirvana fallacy / the perfect solution fallacy. Someone doesn’t need to tell you what their ideal house is for them to say they were prefer a house without termites vs. a house with termites. Similarly, someone doesn’t need to tell you what their ideal global temperature is for them to tell you they prefer it below 1.5 degrees above 1850-1900 vs. at least 1.5 degrees above 1859-1900. You like making the perfect the enemy of the good to suit your policy bias.

And it’s also fallacious trolling to ask ‘under which metric are we worse off than 1850?’. That commits the single cause fallacy. Many factors contributed to us being better off than in 1850, such as better sanitation, vaccines, GMOs, etc. That does not prevent anthropogenic climate change (ACC) from having a negative effect. The impact of ACC is determined with vs. without ACC, not by comparing now to 1850 without accounting for many other confounders that differ between now vs. 1850. To say otherwise is as ridiculous as saying machine guns don’t harm people now, by saying we’re better off now than in 1500 when there were no machine guns, while willfully ignoring the other confounders that changed between 1500 vs. now.

Folks have corrected on you on this for months (if not years), but you persist anyway, as per trolling. No doubt you’ll continue with this in the future, acting like no one has ever debunked your script. That’s how persistent denialism works.

Keith Woolard, I dont find anything you write offensive. That label applies to KIA. I dont have nothing more to add because AS reply suffices perfectly well.

You completely misrepresent what I have said Atomsk’s Sanakan. I am asking which is the best climate? That is the metric I am after.

You say below 1.5 is better than above……Why?

There’s that bad faith again, Keith Woollard. I didn’t say below 1.5 degrees is better. I said saying that does not commit one to answering your malformed question on what the ideal temperature is. Let me when you can finally honestly admit that, and when you finally decide to stop committing the nirvana fallacy.

“The nirvana fallacy is the informal fallacy of comparing actual things with unrealistic, idealized alternatives.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nirvana_fallacy

KW: . I am asking which is the best climate?

BPL: The climate as close as possible to the one all our agriculture and civilization grew up under. For that, mean global annual surface temperature should be close to 287 K.

Atomsk’s Sanakan says

12 Jan 2026 at 12:06 PM

No, Keith Woollard, it’s just trolling that commits the nirvana fallacy / the perfect solution fallacy.

Keith Woollard says

12 Jan 2026 at 10:35 PM

You completely misrepresent what I have said Atomsk’s Sanakan. I am asking which is the best climate? That is the metric I am after.

Atomsk’s Sanakan completely misrepresents what everyone says here, all the time.

But no one seems to care in the least about that. He keeps on lying and trolling disrupting the entire forum. A late comer to these parts all his other pastures must have dried up.

BUt if this the kind of patron Real Climate seeks, then so be it. It’s on them, no one else.

Killian reminded everyone what this place is like for decades. Atomsk’s Sanakan makes it ten times worse then ever; while Piotr destroys any semblance of decency and equanimity as well. His forte. Atomsk’s Sanakan knows nothing about climate science and has no skills in it. He’s just a well read Lawyer prosecuting a case. His own. That he lies and distorts everything so much kind of proves that analogy might even be true.

They’d be better off rid of him. Buy you can’t put wise heads on young shoulders.

Unfortunately, I am traveling, so y’all are victim to the tiny cell phone keyboard and my fat fingers.

Many people who pose the question “But what’s the best climate,” are in fact trolling. However, let us give KW benefit of the doubt.

There is in fact economic data looking at the effect of temperature on economic growth, and this data does in fact suggest there is an optimal temperature range for GDP growth. Unsurprisingly it is the range found in latitudes 40-60 deg. Moreover, warmer temperatures decrease growth significantly (been a while since I looked, but I’m remembering ~1 percentage point per degree of average temp). Salubrious and pestilential climates do exist.

Wow, Atomsk, that’s really being pedantic. You are correct, you didn’t say that below 1.5 is better than above, so I will address my question to the mythical person that has said that (i.e. the vast majority of the people reading this, and the 45,000 attendees at CoP21)

Why?

BPL,

Really? So you’re saying the historical natural climate is preferable?

That’s odd, considering that for at least the last couple of millennia we’ve been actively trying to modify it. Should we tell farmers to stop using greenhouses? (obviously I won’t mention CO2 being pumped in) That orchards should never use frost protection? Or that people shouldn’t live in artificially heated homes?

Perhaps you should also inform the WHO that they’re mistaken—that 13.9°C is optimal, rather than the 18°C minimum they recommend, or the 20°C advised for vulnerable people.

Deniers, Doomers – bedfellows strange no more. Both try to discredit IPCC and climate science, both attack renewables, DAC and net zero, both use the all-or-nothing fallacy to dismiss the sense of mitigation of AGW, both disparage using existing technologies, market mechanisms and policies reducing the AGW. For fundamentalists there is nothing worse than a moderate, and that’s why Data vigorously defends his opposite – the long-term denier Keith Woollard., and before defended denier Ken Towe. The enemy of my moderate enemy is my friend:

Data, in defence of Keith Woollard: Atomsk’s Sanakan completely misrepresents what everyone says here, all the time.

The latest example of Data’s projections of his actions onto his opponents, confirmation bias, triumph of ego over values (defending one’s ego at the cost of aligning oneself with the people from the opposite extreme). That and thrown in for a good measure, a Freudian slip later in the thread. Data – a walking, talking, psychological cliche ! ;-)

P.S. What and your Woollard try to disparage as “misrepresentation” – is drawing a falsifiable logical conclusion that neither Woollard nor you, were able to to counter with a MORE plausible counter-explanation.

Keith Woollard, you’re deflecting from the fact that your nirvana fallacy has been exposed. You’re likely doing that so you can resort to that fallacy later, as you’ve done on Real Climate for months, if not years.

Again: your questions on ‘best’ or ‘perfect’ climate/temperature are malformed and commit the nirvana fallacy. No one is under any obligation to answer them, anymore than someone is required to explain their ‘best’ or ‘perfect’ house when they explain to an exterminator that they want a house without termites vs. with termites. One can say ‘X is better than Y’ without explaining an idealized Z that’s best or perfect.

So these are malformed questions meant to troll people:

I wanted you to see this RC, Gavin:

Hickey, J. (2025). Artificial stepwise increases in homogenized surface air temperature data invalidate published climate warming claims for Canada. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18039553

[Response: Classic case of confirmation bias. Let’s posit that Eastern Canada had some systematic artifact in operating methods/equipment or recording protocols in 1998. What would one expect? You would expect that this would not be seen in neighbouring stations in the US, or Greenland, or elsewhere in the Northern Hemisphere. Unfortunately for this thesis, pre-1998 and post 1998 changes are actually comparable across all these places. The fact is that 1998 was an exceptional year in terms of temperature anomalies, mainly due to the impacts of the 1997/8 super El Niño event (something oddly not mentioned in this document). It is clear in the raw data as well as the homogeneised data, but it sits in the context of a global trend. It is very easy to pretend that there is no trend by cherry picking periods for a linear analysis – indeed, the ‘escalator’ graphic made by Skeptical Science has been lampooning this for years, but basing conclusions on what is essentially just a vibe is not particularly sensible. Sorry – there is nothing here. – gavin]

OK, thanks Gavin.

Still without that 1998 step the trend is not statistically distinguished from zero for 1948-2018 in Canada.

This would mean that the surface temperature is not determined by changing radiation balance from increasing CO2, but rather predominantly determined by ocean-atmosphere dynamics mainly believed to be the result of variations in solar irradiance.

This is my paper on radiation balance: Rancourt, D. G. (2011). Radiation physics constraints on global warming: CO2 increase has little effect (1.1). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17202570

[Response: There is no time series (trend + noise) that you couldn’t play this game with and convince yourself there is no trend. It’s numerological pseudo-science. – gavin]

in Re to Denis Rancourt, 2 Jan 2026 at 11:11 AM,

https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2025/12/1-5oc-and-all-that/#comment-843392

Dear Dr. Rancourt,

Different from Dr. Schmidt who addressed solely your opinion regarding the alleged absence of a temperature trend in Canada during the last several decades, I would like to ask a question to your 2011 article.

It appears that based on your assumption that the energy fluxes through Earth atmosphere and surface as reported in literature are incorrect, you inferred a significantly higher IR opacity of the atmosphere than commonly assumed, and therefrom you construe your conclusions that CO2 absorption bands are almost completely saturated and that changes in the atmospheric CO2 concentration must have much smaller influence on Earth radiative (im)balance than generally assumed. Am I right?

If so, my question reads:

Are you sure that the mainstream climate science derived all the values of the energy fluxes (and/or the (allegedly too low) infrared atmospheric opacity / incomplete saturation in CO2 absorption bands) solely (and improperly) from Earth albedo observations (as you seem to suggest), instead e.g. from independent spectroscopic laboratory studies of greenhouse gases, their detailed validation by theoretical quantum mechanical computations, and from detailed knowledge of the height profile of their atmospheric concentration?

Thank you in advance for a comment and best regards

Tomáš

Denis Rancourt “ Still without that 1998 step the trend is not statistically distinguished from zero for 1948-2018 in Canada.”

Explain then why Zhang et al. (2019): Changes in Temperature and Precipitation Across Canada; Chapter 4 in Bush, E. and Lemmen, D.S. (Eds.) Canada’s Changing Climate Report. Government of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, pp 112-193.

for practically the same data range – found the opposite:

“Between 1948 and 2016, the best estimate of mean annual temperature increase is 1.7ºC for Canada as a whole and 2.3ºC for northern Canada.”

And here is a graph for it: https://changingclimate.ca/CCCR2019/chapter/4-0/ In this graph, there are TWO variables plotted: blue are annual temp anomalies, and black are 11-year running average anomalies: To illustrate the difference in the variability of each = here are data for T anomalies for several years:

yr 1949 1950 1951 1952

blue -0.02 -1.96 +0.65 -0,79 std. dev=0.385

black -0,24 -0.13 -0.13 -0.17 std. dev=0.035

As expected. the black variable, being 11-year avg., has MUCH smaller standard deviation.

In the graph we see why the trend of the black line is significantly different than zero, the warming trend is strong compared to the tiny noise (the small fluctuations of the black line)). In contrast. the blue line is very noisy – hence the trend of the blue is small comparing to the very large year to year noise of blue line.

Of those two – ONLY the black line – the 11-running average, is informative of the climate – over long time-scale, the warming trend overpowers the tiny residual fluctuations, left after averaging out the short term variability by the 30 year (climatic) averaging. And it is at this timescale at which CO2 increases enough to have an influence on global T.

In contrast, your analysis of the blue line tells us nothing about climate trends, in fact it is a “negative knowledge” – as it actively misleads us about climate – it claims to have disproven the effect of CO2 on climate, I quote:

Denis Rancourt: “ This would mean that the surface temperature is not determined by changing radiation balance from increasing CO2” and attributes all changes to “ variations in solar irradiance” (no evidence provided).

And to suggest to the reader a scientific rigour, this misinformation uses scientific language:

“the trend is not statistically distinguished from zero for 1948-2018 in Canada” and suggests scientific credibility of the author disporing of the role of CO2 by referring to the professionally looking reference (“Rancourt, D. G. (2011). Radiation physics constraints on global warming: CO2 increase has little effect (1.1). Zenodo”)

I, when proven wrong, change my opinions. What do you do, Mr. Rancourt?

One of the oldest “lying with statistics” methods is to start at a local max and end at a local min and declare “no trend”. The second oldest is to take too short a period and declare “no trend” in absolute defiance of hypothesis testing logic. The third oldest is to use statistical insignificance to assert “to underlying trend” again in defiance of HT logic.

A rather newer method is self-citing non-peer-reviewed work with ZERO recorded citations after now 15 years as meaning anything at all scientifically.

Hey, but he managed to click-bait his paper, at least.

Yup, and he can claim he got a response from Gavin Schmidt, without specifying that the response was dismissive. That counts for sumpin, dunnit?

Thanks for the link to the Hickey 2025 paper. The email correspondence is interesting. Perhaps the work will lead to greater efforts by Environment and Climate Change Canada (formerly Environment Canada) to identify specific dates of change from manual to automated observations within the metadata archives. Facts are better than stats.

Denis, quite interesting to look at the bios your group (https://correlation-canada.org/about/ ) , and the fact that you and your organization seems to have put a lot of effort into churning out preprints denying the harms from the SARS-CoV-2 virus. It seems they didn’t ever make it through any peer review, though.

I see that before you made greenhouse warming disappear, you made the COVID pandemic in Canada vanish.. Miraculous.

“Analysis of all-cause mortality by week in Canada 2010- 2021, by province, age and sex: There was no COVID-19 pandemic, and there is strong evidence of response- caused deaths in the most elderly and in young males.”

August 2021 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.14929.45921

Authors: Denis G Rancourt, Marine Baudin, Jérémie Mercier

In a different preprint’s abstract, you claim that there’s no correlation between COVID vaccinations in the USA and changes in death rates from the disease – have you read the peer reviewed studies that compared post-availability death rates from COVID-19 in Ohio and Florida, which noted that deaths dropped off sharply in counties that trended more towards Biden and death rates stayed higher in counties that hewed more to vaccine-denier Trump and DeSantis?

In another of your group’s output the abstract claims:

https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.11570.32962

It goes on in a way that would be amusing but my brother lost TWO middle-aged in-laws in the same week to COVID. Not seniors, but parents and both listened to nonsensical misinformation that said vaccines weren’t needed and COVID-19 was just like the flu. They weren’t suffering the stress of government public health efforts – they died because they’d believed lies.

Regarding seasonal structure – you might not have spent much time in the US Southeast, which trended anti-precautions during the pandemic, yet also are driven to indoor gatherings when summer temperatures get too much to bear. I’ve been there, I’ve seen it.

I note that ResearchGate states your name as lead author for the COVID pre-prints but that you are not listed in ResearchGate or have not claimed the work – you might want to address that at some time.

I note that the third author has a website where he advertises a liver cleanse and also this:

So you’ve moved on from presenting the global pandemic as a hoax?

Pardon my stating an opinion, but your group appears biased against public health measures and the medical/epidemiological body of evidence, and now might be trying your hand at yet another of the innumerable attempts to pretend a couple hundred years of physics, chemistry, etc. is all wrong.

Many climate denial groups pivoted to denying a global pandemic once the seriousness of it was evident, your team appears at least to have run in the opposite direction. This is just my opinion, but without peer-review, all those pre-prints on COVID are, too.

As a former Cdn academic myself I knew all about but did not mention his rather chequered history of “research” and “teaching” above which is mostly 100% political activism It is easily googled and/or wiki’ed.

He managed to pull off two rather unimaginably difficult Cdn tricks first of getting many of his own colleagues to give up support for his so-called academic freedom so much so the CAUT supported the university’s firing* and second of being convicted in civil court of defamation against a fellow faculty member. I think he may be the only person in Cdn history to manage this particular exacta.

I might add that Sen. Inhofe likes his climate “research”.

As for those who say this is all ad hom, well there is absolutely no actual science to discuss so the “hom” is the only thing in play TO discuss.

______

*Not even Marlene Webber at my own institution managed to do that! We quite rightfully were censured by CAUT for many years for the bad faith actions of the admin.

@jgnfld – thanks for the background, I’d been unaware of him until I started trying to learn the qualifications of the author (also in his organization) of the climate thing. Nonsense about climate change? Not as big an issue at this point since nonsense has already been deeply set in many people’s minds since the oil industry first had valid confirmation of the dangers of continued use of their products. And the solutions to fossil burning are falling into place – too slowly, but the end will happen.

Infectious disease is different since there’s always the next one evolving or encountering humans as we spread into formerly uninhabited areas. We’d been winning many battles – the development of the mRNA vaccines was nearly miraculous, so people trying to deliberately misinform for their own purposes hits me hard.

Long covid ended my mother’s independence when it affected brain, not lungs. My brother’s in-laws lived in two separate states and both died long after vaccines were available – their mom had been released from a month in the hospital the same week they both died. Imagine what that family has been going through, dealing with loved ones who died because they’d been told vaccination was needless, and they fell for the lie..

I and many family members live in northern big cities, and the sound of ambulances was far too common in 2020. A nephew drove an ambulance for a big city hospital – started about a month before the pandemic hit.. And a friend volunteered to do vaccinations in Idaho – she can tell stories of the people slinking in for a shot, with their MAGA shirts or hats, after losing a few too many family members of their own – sometimes watching loved ones die while still denying what it was killing them..

As you said, there’s no science in what I looked at yesterday, but this isn’t an ad hom against people who clearly aren’t doing science when they claim they are – it’s just an informal peer review.

1.5ºC and all that

28 Dec 2025 by Gavin

The Paris Agreement temperature limits are a little ambiguous and knowing where we are is tricky.

The desire to keep global temperature rises since the pre-industrial, ideally below 1.5ºC and definitely below 2.0ºC, is a little bit complicated by the lack of definition in what constitutes the pre-industrial, uncertainties in what the temperature was in the pre-industrial, and an ambiguity in what counts as exceeding these limits.

https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2025/12/1-5oc-and-all-that/

Data responds: the Paris Agreement temperature limits are explicit and well-defined.

The Paris Agreement temperature limits were explicitly adopted at COP21 in 2015 (Decision 1/CP.21), so the “desire to keep below 1.5 °C” is not ambiguous — it is a clear policy commitment. It’s all already there — in COP21 and SR15. Just add logic and common sense.

To maintain consistency with SR15, the pre-industrial GMST baseline should be defined using the datasets available at the time—HadCRUT4, GISTEMP, Cowtan–Way, and NOAA—covering 1850–1900. For current estimates, the best-practice approach is to use these long-term datasets where available (HadCRUT5, NOAA v6, Berkeley Earth), add reliable datasets such as NASA-GISS and ERA5, adjust them to the same 1850–1900 reference, and calculate a mean across them all. For any 30-year centered period extending into the future, simply extend the recent multi-decadal trend linearly; no speculative projections or alternative datasets are required.

This method ensures continuity with the original SR15 analysis, avoids unnecessary complexity, and transparently identifies when GMST crosses 1.5 °C. Introducing new or untested datasets, such as DCENT, is unnecessary and adds uncertainty without improving comparability. Importantly, the 1.5 °C crossing is primarily a political event—it matters for COP21 Paris Agreement reporting and framing, not for fundamental climate science or calculations.

References:

SR15 Summary for Policymakers

https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/spm/

About https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/about/

Core Concepts Central to this Special Report-Box SPM.1

https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/spm/spm-core-concepts/

SR15 Figure SPM.1

https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/02/SPM1_figure-final.png

IPCC adopted outline SR15

https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/03/l2_adopted_outline_sr15-2.pdf

Adoption of the Paris Agreement-COP21

https://unfccc.int/files/home/application/pdf/decision1cp21.pdf

Being aware of these historical documents should clear up most confusions.

Those eager to shut down all honest information are delighted that we are all quibbling over definitions and detail. Bookburning, forcing educational institutions to give time to lies, extortion, shutting down progress, bullying, massive subsidies and tax breaks to delusional billionaires, these are our reality in the US, rapidly being exported around the world where the wannabe bosses see they only need to get us fighting with each other to ‘win’.

Promises to do something by some specified future date are useless if they are not accompanied by effective action.

Consider the people so angry about Gaza [substitute your preferred issue here] they didn’t bother to vote or voted for pitchforks. Someone rooted in reality would not spend hours on minutiae but get to work doing something useful.

Think of a sand clock. Such a simple thing. We all know what happens every time you turn it upside down.

We can easily have an idea of the size and the shape of the little sand mountain formed and the time it took to travel from one globe to the other.

But if you want to know what happens with each of the sand grains, or when and where little avalanches are going to happen,… good luck.

Denialism has invest huge amounts of money trying to bring science and public to this arena; if you cannot be scientifically sure of what is going to happen to each of the sand grains, you cannot understand and predict what’s going to happen when using the sand clock.

Please, stop wasting time discussing the obvious because we don’t have and answer for all the details in chaos,

There are always very good arguments (apparently) to discuss about the destiny of each sand grains but that knowledge is BS.

https://youtu.be/JxE6XFKOaRM

GW appears to have accelerated significantly according to research by Stefan and Grant.

That pre-print was discussed at length in threads elsewhere:

https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2025/11/unforced-variations-nov-2025/#comment-842447

The main points are that the pre-print does not show statistically significant acceleration of global warming, but instead shows statistical significant acceleration of the adjusted global temperature trend (i.e. the trend after removing the impact of changes in total solar irradiance, ENSO, and volcanic emissions). Using that adjusted trend to project future global temperature trends, as done in the video you cited from Paul Beckwith, likely overestimates future global warming.

Does it. Got any evidence for that then ?

You were already linked to evidence, and it’s stated in their pre-print. Did you read the pre-print, or only watch Beckwith’s video?

I can’t see what you are saying. Is it warning faster or not. 90% isn’t 95% but 90% is significant !

Is it warning faster or not or we can’t tell because the time lines arnt long enough to know to the 95% confidence level we need and if this is the case then we need to wait another 20 years to know.