The Arctic Council’s Arctic Monitoring and assessment Programme (AMAP) recently released a Summary for PolicyMakers’ Arctic Climate Change Update 2024.

[Read more…] about The most recent climate statusClimate science from climate scientists...

I am a senior scientist working at the Norwegian Meteorological Institute with a background from physics. My scientific career started with a degree in Physics with Electronics at UMIST in Manchester (UK), cloud micro-physics at New Mexico Tech (USA), and ocean physics at Atmospheric Oceanic and Planetary Physics (AOPP) at Oxford University (UK). Since then, I have also got heavily involved in the field of statistics, thanks to exciting collaborations with several statisticians.

My primary focus at the Norwegian Meteorological Institute has been towards climate change adaptation, empirical-statistical downscaling and anthropogenic climate change, but I have also worked on problems relating to natural climate variations connected to changes in the sun. I have authored two text books on these topics: Solar Activity and Earth's climate (Praxis/Springer) and Empirical-Statistical Downscaling (World Scientific Publishers).

My experience from the climate science community includes several roles: a contributing author on two past IPCC assessment reports, a person of contact (POC) for World Climate Research Programme's (WCRP) CORDEX project, a coordinating lead author on Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme's (AMAP) report Adapting Actions in a Changing Arctic (AACA, 2017), a councilor for the European Meteorological society (EMS), a member of the EMS communication and media committee, and part of the advisory board for Oxford Research Encyclopedia on climate. I also chair the professional network within the Norwegian trade union for engineer and natural scientists Tekna Klima, dealing with a diverse range of climate solutions.

D. Phil in physics from Atmospheric, Oceanic & Planetary Physics, Oxford University, U.K.

Funding: governmental (Norwegian Science Foundation)

The Arctic Council’s Arctic Monitoring and assessment Programme (AMAP) recently released a Summary for PolicyMakers’ Arctic Climate Change Update 2024.

[Read more…] about The most recent climate statusby rasmus

While there have been some recent set-backs within science and climate research and disturbing news about NOAA, there is also continuing efforts on responding to climate change. During my travels to Mozambique and Ghana, I could sense a real appreciation for knowledge, and an eagerness to learn how to calculate risks connected to climate change.

[Read more…] about Climate change in Africaby rasmus

It’s 20 years since we started blogging on climate here on RealClimate (December 10, 2004). We wanted to counter disinformation about climate change that was spreading through various campaigns. In those days it was an unusual move that prompted a welcome from Nature.

[Read more…] about Twenty years of blogging in hindsightby rasmus

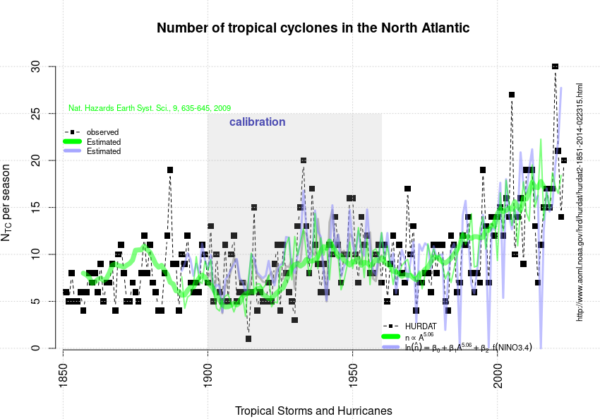

This year’s (2023) tropical cyclone season in the North Atlantic and Caribbean witnessed a relatively high number of named tropical cyclones: 20. In spite of the current El Niño, which tends to give lower numbers. But it appears to follow a historical trend for named tropical cyclones with an increasing number over time.

The curve presented above is an update of the analysis presented in 2020 and posted here on RealClimate.

[Read more…] about 2023 appears to follow an upward trend in the North Atlantic/Caribbean named tropical cyclone countby rasmus

A friend asked me if a discussion paper published on Statistics Norway’s website, ‘To what extent are temperature levels changing due to greenhouse gas emissions?’, was purposely timed for the next climate summit (COP28). I don’t know the answer to his question.

[Read more…] about A distraction due to errors, misunderstanding and misguided Norwegian statisticsby rasmus

The fifth international conference on regional climate (ICRC 2023), organised by World Climate Research Programme’s (WCRP) coordinated downscaling experiment (CORDEX), has just completed. It was a hybrid on-site/online conference with hubs in both Trieste/Italy (hosted by the International Centre on Theoretical Physics, ICTP) and Pune/India.

The hybrid set-up, with video links between the two hubs and digital attendence through zoom, was a change from previous ICRCs held in ICTP (2011), Brussels (2013), Stockholm (2016), and Beijing (2019). It worked impressively well, and the CORDEX ICRC 2023 streaming is available from the WCRP CORDEX YouTube channel.

It seems as an eternity since the previous ICRC before the COVID pandemic, so I was curious to see how things have progressed since then. It was also interesting to compare my impressions from this conference with my blog posts here on RealClimate from the first ICRC in Trieste, the second in Brussels, the third ICRC in Stockholm, I see that questions concerning uncertainty and added value are still being debated.

by rasmus

Media awareness about global warming and climate change has grown fairly steadily since 2004. My impression is that journalists today tend to possess a higher climate literacy than before. This increasing awareness and improved knowledge is encouraging, but there are also some common interpretations which could be more nuanced. Here are two examples, polar amplification and extreme rainfall.

[Read more…] about Old habitsby rasmus

The World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) Global Climate Observing System (GCOS) and Copernicus Climate Change Services (C3S) both provide sets of global climate statistics to summarise the state of Earth’s climate. They are indeed valuable indicators for the global or regional mean temperature, greenhouse gas concentrations, both ice volume and area, ocean heat, acidification, and the global sea level.

Still, I find it surprising that the set does not include any statistics on the global hydrological cycle, relevant to rainfall patterns and droughts. Two obvious global hydro-climatological indicators are the total mass of water falling on Earth’s surface each day P and the fraction of Earth’s surface area on which it falls Ap.

[Read more…] about Area-based global hydro-climatological indicatorsby rasmus

Do the global climate models (GCMs) we use for describing future climate change really capture the change and variations in the region that we want to study? There are widely used tools for evaluating global climate models, such as the ESMValTool, but they don’t provide the answers that I seek.

I use GCMs to provide information about large-scale conditions, processes and phenomena in the atmosphere that I can use as predictors in downscaling future climate projections. I also want to know whether the ensemble of GCM simulations that I use provides representative statistics of the actual regional climate I’m interested in.

[Read more…] about Evaluation of GCM simulations with a regional focus.by rasmus

The summary for policymakers of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) sixth synthesis report was released on March 20th (available online as a PDF). There is a recording of the IPCC Press Conference – Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report for those who are interested in watching an awkward release of the report.

It strikes me that the IPCC perhaps assumes that everyone is climate literate and are up to speed on climate change. While many journalists clearly got the message, expressed through news reports though e.g. the Guardian and Washington Post, I doubt that relevant leaders were swayed. One problem may be that journalists do not carry as much weight as scientists.

[Read more…] about The summary for policymakers of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change sixth assessment reports synthesis1,367 posts

11 pages

244,108 comments