We were pleased to hear from the University of Arizona’s Jeff Kargel that the Times Atlas folks are now updating their atlas of Greenland. As we reported earlier, the first edition was completely in error, and led to some rather bizarre claims about the amount of ice loss in Greenland. Kargel reports that HarperCollins (publisher of the Times Atlas) has now fully retracted their error and has produced a new map of Greenland that will be made available as a large-format, 2-side map insert for the Atlas and will also be available free online. Meanwhile, Kargel and colleagues have produced their own updated small-scale map and have written a paper that includes both their new map and a description of the incident that led up to it. Kargel was instrumental in pushing the cryosphere community to send a strong message to the publishers that they needed to correct their mistake. (A pre-print of the paper, currently under review and under public discussion on Cryolist, is available here.)

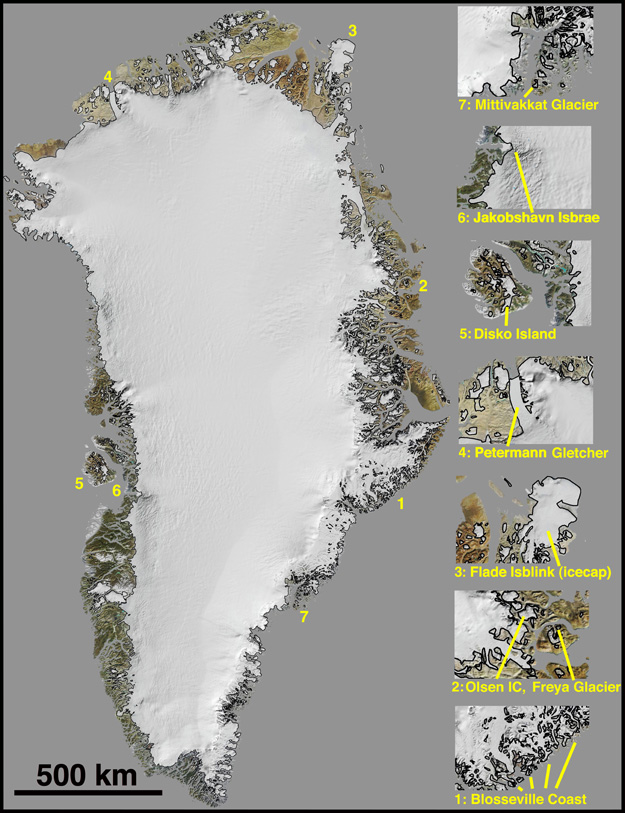

Figure 1 in Kargel et al. (2011) generated by a collaboration of the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS) and the Programme for Monitoring of the Greenland Ice Sheet (PROMICE) with the Polar Geospatial Center Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Minnesota. Contact: Michele Citterio (GEUS) for questions about the glacier outlines or Paul Morin (UMinn.) for questions about the MODIS base image mosaic.

Figure 1 in Kargel et al. (2011) generated by a collaboration of the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS) and the Programme for Monitoring of the Greenland Ice Sheet (PROMICE) with the Polar Geospatial Center Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Minnesota. Contact: Michele Citterio (GEUS) for questions about the glacier outlines or Paul Morin (UMinn.) for questions about the MODIS base image mosaic.

HarperCollins is to be commended for listening to the scientific community and producing a corrected map. Unfortunately, and despite recent events demonstrating that popular allegations against climate scientists are all wrong, HarperCollins still says on their web site that it’s all the scientists’ fault for not being clear (“The one thing that is very apparent is that there is no clarity in the scientific and cartographic community on this issue”,they write). Hmm. Our own view is that anyone flying over Greenland en route to Europe from North America would instantly have recognized a problem with the Times Atlas (assuming they knew their location of course). As Kargel and colleagues write in their paper:

“Distinguishing manifest, ignorable nonsense from falsehoods that might take root in the public mind is difficult, but the magnitude of and apparent authority behind this particular mistake seemed to warrant a rapid and firm response. The eventually constructive reaction of HarperCollins, which not only withdrew its mistaken claim but also produced a new map to be included in the Times Atlas as an insert, shows the value of such a response. No less than grotesque trivialization, grotesque exaggeration of the pace or consequences of climate change needs to be countered energetically.”

Nevertheless, they caution that “scientists cannot possibly challenge all of the innumerable misunderstandings and misrepresentations of their work in public discourse.”

Well said. Of course, many scientists can do more, and we encourage all of our colleagues to speak publically about their research and, as the international glaciological research community did in this case, to try to correct misconceptions. At the same time, hopefully, HarperCollins will catch on and recognize that being scientifically literate is not just scientists’ responsibility, but is everyone’s responsibility.

It would not surprise me if the denialists would deny the existence of the new book by Haydn Washington and John Cook (

It would not surprise me if the denialists would deny the existence of the new book by Haydn Washington and John Cook (

The new novel Solar by Ian McEwan, Britain’s “national author” (as many call him) tackles the issue of climate change. I should perhaps start my review with a disclosure: I’m a long-standing fan of McEwan and have read all of his novels, and I am also mentioned in the acknowledgements of Solar. I met McEwan in Potsdam and we had some correspondence while he wrote his novel. Our recent book

The new novel Solar by Ian McEwan, Britain’s “national author” (as many call him) tackles the issue of climate change. I should perhaps start my review with a disclosure: I’m a long-standing fan of McEwan and have read all of his novels, and I am also mentioned in the acknowledgements of Solar. I met McEwan in Potsdam and we had some correspondence while he wrote his novel. Our recent book