This month’s open thread…

… continued here.

Climate science from climate scientists...

by group

This month’s open thread…

… continued here.

by eric

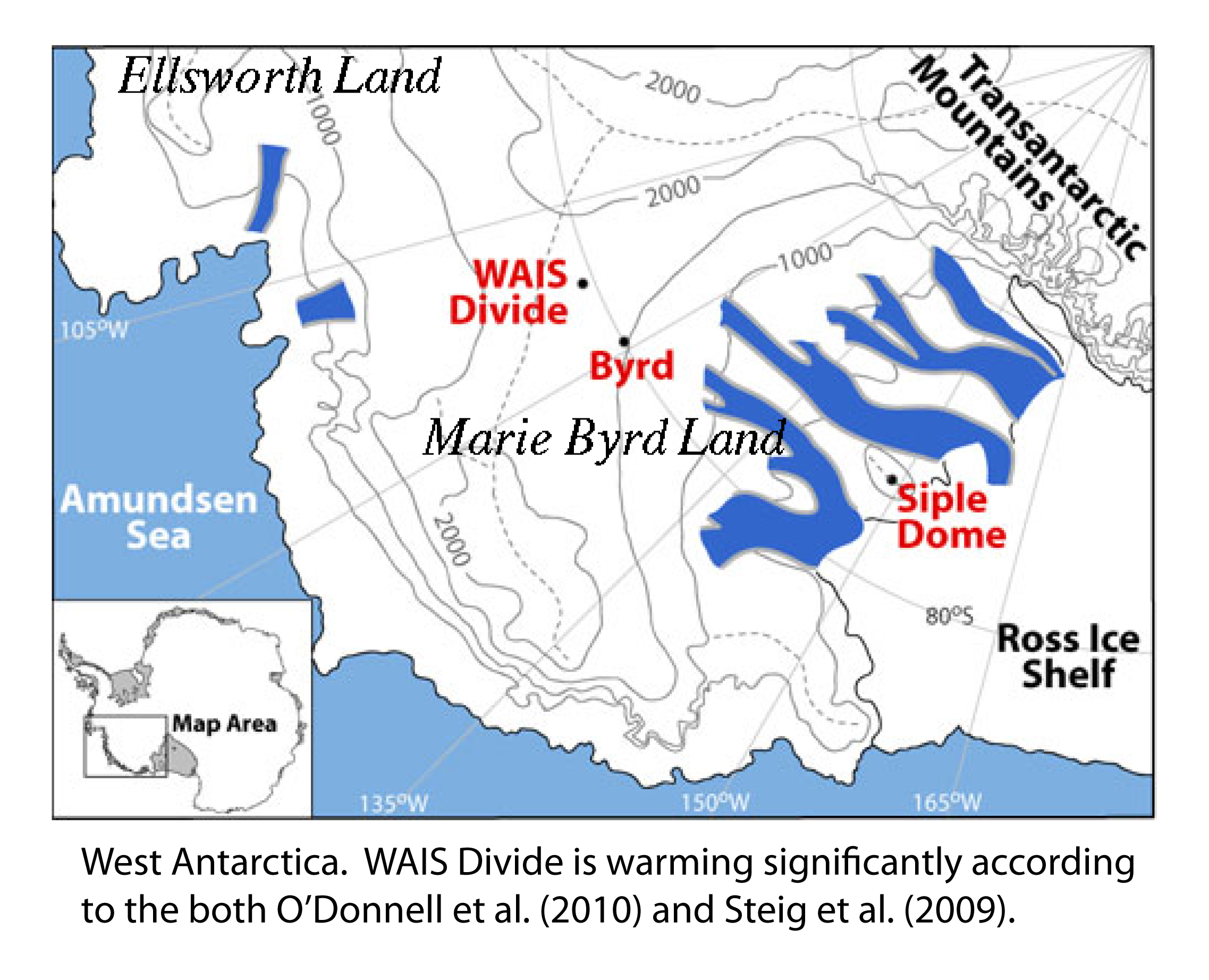

The temperature reconstruction of O’Donnell et al. (2010) confirms that West Antarctica is warming — but underestimates the rate

Eric Steig

At the end of my post last month on the history of Antarctic science I noted that I had an initial, generally favorable opinion of the paper by O’Donnell et al. in the Journal of Climate. O’Donnell et al. is the peer-reviewed outcome of a series of blog posts started two years ago, mostly aimed at criticizing the 2009 paper in Nature, of which I was the lead author. As one would expect of a peer-reviewed paper, those obviously unsupportable claims found in the original blog posts are absent, and in my view O’Donnell et al. is a perfectly acceptable addition to the literature. O’Donnell et al. suggest several improvements to the methodology we used, most of which I agree with in principle. Unfortunately, their actual implementation by O’Donnell et al. leaves something to be desired, and yield a result that is in disagreement with independent evidence for the magnitude of warming, at least in West Antarctica.

In this post, I’ll summarize the key methodological changes suggested by O’Donnell et al., discuss how their results compare with our results, and the implications for our understanding of recent Antarctic climate change. I’ll then try to make sense of how O’Donnell et al. have apparently wound up with an erroneous result.

In this post, I’ll summarize the key methodological changes suggested by O’Donnell et al., discuss how their results compare with our results, and the implications for our understanding of recent Antarctic climate change. I’ll then try to make sense of how O’Donnell et al. have apparently wound up with an erroneous result.

[Read more…] about West Antarctica: still warming

by group

A few items of interest this week.

Paleoclimate:

1. A new study by Spielhagen and co-authors in Science reconstructs temperatures of North Atlantic source waters to the Arctic for the past two millennia, adding another very long-handled Hockey Stick to the ever-growing league.

2. From last week, an article in Science Express by Buntgen et al reconstructing European summer temperature for the past 2500 years, finding that recent warming is unprecedented over that time frame, and providing some historical insights into the societal challenges posed by climate instability (listen here for an interview with mike about the study on NPR’s All Things Considered).

3. The team of ice core researchers at WAIS Divide reaches its goal of 3300 meters of ice. [WAIS Divide, central West Antarctica, is a site of significant warming in Antarctica, over at least the last 50 years, a result recently confirmed by the study of O’Donnell et al. (2010); Stay tuned for more on the that soon].

Other Miscellaneous Items:

1. More in Nature on data sharing.

2. A great primer in Physics Today on planetary energy balance from our very own Ray Pierrehumbert (link to pdf available here).

3. Now shipping are David and Ray’s The Warming Papers and Ray’s Principles of Planetary Climate.

by Gavin

As we did roughly a year ago (and as we will probably do every year around this time), we can add another data point to a set of reasonably standard model-data comparisons that have proven interesting over the years.

[Read more…] about 2010 updates to model-data comparisons

by Gavin

Last Monday, I was asked by a journalist whether a claim in a new report from a small NGO made any sense. The report was mostly focused on the impacts of climate change on food production – clearly an important topic, and one where public awareness of the scale of the risk is low. However, the study was based on a mistaken estimate of how large global warming would be in 2020. I replied to the journalist (and indirectly to the NGO itself, as did other scientists) that no, this did not make any sense, and that they should fix the errors before the report went public on Thursday. For various reasons, the NGO made no changes to their report. The press response to their study has therefore been almost totally dominated by the error at the beginning of the report, rather than the substance of their work on the impacts. This public relations debacle has lessons for NGOs, the press, and the public.

[Read more…] about Getting things right

by Gavin

Despite what is often claimed, climate scientists aren’t “just in it for the money”. But what scientists actually do to get money and how the funding is distributed is rarely discussed. Since I’ve spent time as a reviewer and on a number of panels for various agencies that provide some of the input into those decisions, I thought it might be interesting to discuss some of the real issues that arise and the real tensions that exist in this process. Obviously, I’m not going to discuss specific proposals, calls, or even the agencies involved, but there are plenty of general insights worth noting.

[Read more…] about Reflections on funding panels

by group

Guest commentary from Michael Tobis and Scott Mandia with input from Gavin Schmidt, Michael Mann, and Kevin Trenberth

While it is no longer surprising, it remains disheartening to see a blistering attack on climate science in the business press where thoughtful reviews of climate policy ought to be appearing. Of course, the underlying strategy is to pretend that no evidence that the climate is changing exists, so any effort to address climate change is a waste of resources.

A recent piece by Larry Bell in Forbes, entitled “Hot Sensations Vs. Cold Facts”, is a classic example.

[Read more…] about Forbes’ rich list of nonsense

by group

After perusing the comments and suggestions made last week, we are going to try a new approach to dealing with comment thread disruptions. We are going to try and ensure that there is always an open thread for off-topic questions and discussions. They will be called (as this one) “Unforced Variation: [current month]” and we will try and move all off-topic comments on other threads to these threads. So if your comment seems to disappear from one thread, look for it here.

Additionally, we will institute a thread for all the troll-like comments to be called “The Bore Hole” (apologies to any actual borehole specialists) that won’t allow discussion, but will serve to show how silly and repetitive some of the nonsense that we have been moderating out is. (Note that truly offensive posts will still get deleted). If you think you’ve ended up there by mistake, please let us know.

With no further ado, please talk about anything climate science related you like.

by group

What with holiday travel, and various other commitments, we’ve missed a few interesting stories over the last week or so.

First off, AGU has posted highlights from this year’s meeting – mainly the keynote lectures, and there are a few interesting presentations for instance from Tim Palmer on how to move climate modelling forward, Ellen Mosley-Thompson on the ice records, and David Hodell on abrupt climate change during the last deglaciation. (We should really have a ‘videos’ page where we can post these links more permanently – all suggestions for other videos to be placed there can be made in the comments).

More relevant for scientist readers might be Michael Oppenheimer’s talk on the science/policy interface and what scientists can usefully do, in the first Stephen Schneider Lecture. There was a wealth of coverage on AGU in general, and for those with patience, looking through the twitter feeds with #agu10 shows up a lot of interesting commentary from both scientists and journalists. Skeptical Science and Steve Easterbrook also have good round ups. [edited]

Second, there was a great front page piece in the New York Times by Justin Gillis on the Keeling curve – and the role that Dave Keeling’s son, Ralph, is playing in continuing his father’s groundbreaking work. Gillis had a few follow-up blogs that are also worth reading. We spend a lot of time criticising media descriptions on climate change, so it’s quite pleasing to be praising a high profile story instead.

Finally, something new. Miloslav Nic has put together a beta version of an interactive guide to IPCC AR4, with clickable references, cited author (for instance, all the Schneiders) and journal searches. This should be a very useful resource and hopefully something IPCC can adopt for themselves in the next report.

Back to normal posting soon….

by rasmus

Last June, during the International Polar Year conference, James Overland suggested that there are more cold and snowy winters to come. He argued that the exceptionally cold snowy 2009-2010 winter in Europe had a connection with the loss of sea-ice in the Arctic. The cold winters were associated with a persistent ‘blocking event’, bringing in cold air over Europe from the north and the east.

1,386 posts

11 pages

248,569 comments